Here is an extended, in-depth introduction to your leadership journey through the Musée Rodin, following Peter de Kuster’s Hero’s Journey story model with 12 archetypes. This introduction weaves together the context of leadership storytelling, the power of narrative in organizational life, the unique approach of Peter de Kuster, and the transformative potential of engaging with art and story in the heart of Paris. It draws on the provided sources and expands on the psychological, emotional, and creative dimensions of this journey, setting the stage for the deep exploration that follows.

Introduction: The Art and Power of the Leadership Journey

I. The Timeless Call to Story

Since the dawn of civilization, humans have gathered around fires, in temples, in city squares, and in boardrooms to share stories. Stories are how we make sense of the world, how we transmit wisdom, how we inspire action, and how we remember who we are. Every culture, every community, every organization is built on stories-stories of origin, of struggle, of triumph, of failure, and of hope. But perhaps the most powerful story of all is the one we tell ourselves about our own journey: the story of who we are, why we are here, and what we are called to do.

In times of uncertainty and change, when the old maps no longer serve and the future seems unclear, we instinctively turn to story for guidance. As Peter de Kuster, founder of The Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey projects, observes, “We fall back, in these crazy and chaotic times, on the command-and-control model of leadership-a model that no longer works. What we need instead are stories: stories that spark action, build trust, transmit vision, and help people work together to create the future”.

II. The Hero’s Journey: A Universal Map for Transformation

The Hero’s Journey, as articulated by Peter de Kuster, is a universal map for transformation. It is the archetypal story structure that underlies myths, legends, and great works of art across cultures and centuries. At its heart, the Hero’s Journey is a journey of change: leaving the familiar, facing trials and tests, receiving guidance, enduring ordeals, seizing the reward, and returning home transformed-with a gift to share.

This journey is not just for mythical heroes or literary protagonists. It is the journey of every leader, every creative professional, every individual who seeks to make a difference in the world. It is the journey of innovation, of entrepreneurship, of personal and organizational growth. And it is a journey that can be consciously chosen, shaped, and lived.

Peter de Kuster’s approach to the Hero’s Journey is both practical and profound. Drawing on decades of experience in storytelling, marketing, and leadership development, he offers a hands-on guide for unleashing the power of narrative in business and life. His work is grounded in the belief that “everyone can lead by using stories to effect change”-and that the right story at the right time can make an audience “stunningly vulnerable to a new idea”.

III. Why Storytelling Matters for Leaders

In a world of constant change, complexity, and ambiguity, leadership is less about command and control and more about meaning-making, vision, and connection. The most effective leaders are not just experts or authorities; they are storytellers-people who can articulate a compelling vision, build trust, foster collaboration, and inspire action through story.

Storytelling is one of the few ways to handle the most important and difficult challenges of leadership:

- Sparking action: Stories can ignite enthusiasm for change, helping people see what is possible and why it matters.

- Building trust: Stories communicate who you are, what you value, and why you can be trusted.

- Transmitting vision: Stories help people imagine the future, see their role in it, and commit to making it real.

- Fostering collaboration: Stories bring people together, helping them understand each other, work through conflict, and achieve shared goals.

- Overcoming resistance: Stories can neutralize naysayers, address fears, and create space for innovation.

As Peter de Kuster explains, “The Leader’s Story shows how successful leaders use stories to get their ideas across and spark enduring enthusiasm for change. It is a hands-on guide to unleash the power of the business narrative”.

IV. The Power of Archetypes: The 12 Stages of the Journey

The Hero’s Journey is structured around a series of archetypal stages, each representing a key moment in the process of change. These stages are not just steps in a plot; they are universal experiences, inner movements, and leadership challenges. In Peter de Kuster’s model, each stage is associated with a particular archetype-a pattern of behavior, motivation, and energy that can be activated and explored.

The 12 archetypes of the Hero’s Journey are:

- The Innocent (Ordinary World)

- The Seeker (Call to Adventure)

- The Orphan (Refusal of the Call)

- The Sage (Meeting the Mentor)

- The Warrior (Crossing the Threshold)

- The Everyman (Tests, Allies, and Enemies)

- The Lover (Approach to the Inmost Cave)

- The Destroyer (The Ordeal)

- The Creator (Reward/Seizing the Sword)

- The Ruler (The Road Back)

- The Magician (Resurrection)

- The Sage/Everyman (Return with the Elixir)

Each archetype represents a different way of being, a different set of strengths and challenges, and a different lesson to be learned. By engaging with these archetypes-through story, reflection, and creative practice-leaders can access new perspectives, unlock hidden potential, and navigate the complexities of change with greater confidence and wisdom.

V. The Musée Rodin: A Sanctuary for the Leadership Journey

Why the Musée Rodin? Why art? Why Paris?

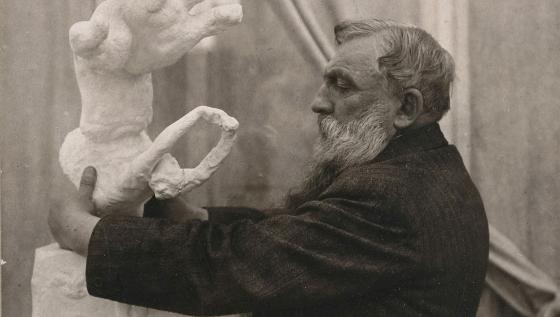

The Musée Rodin, housed in the elegant Hôtel Biron and surrounded by lush gardens, is one of the world’s great sanctuaries of creativity. It is home to the masterpieces of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), the sculptor who revolutionized modern art with his raw, expressive, and deeply human works. Rodin’s sculptures are not just objects of beauty; they are embodiments of struggle, longing, awakening, and transformation. They are stories in stone and bronze-stories of the human condition, of love and loss, of vision and vulnerability.

To walk through the Musée Rodin is to walk through the stages of the Hero’s Journey. Each sculpture is a portal to a different archetype, a different moment in the journey, a different lesson for leaders. By engaging with these works-not just as art, but as mirrors for your own story-you are invited to reflect, to question, to imagine, and to grow.

In the words of Peter de Kuster, “This journey is not just about art; it is about your life, your leadership, your story. You are the storyteller of your own life, and you can create your own legend-or not”.

VI. The Leadership Journey: What Awaits You

Below you’ll find a leadership journey through the Musée Rodin, following Peter de Kuster’s Hero’s Journey story model with 12 archetypes. For each stage, I’ve selected a masterpiece by Auguste Rodin, provided the artist’s name, and offered an explanation from the Hero’s Journey perspective-including questions and exercises to help leaders explore their own story.

What can you expect from this journey?

- A deep dive into the art and science of storytelling: Learn how to use narrative to handle the most important and difficult challenges of leadership: sparking action, building trust, fostering collaboration, and leading people into the future.

- A practical, hands-on approach: Engage with tried and tested tools to shape, structure, and optimize innovation within your projects and organization. Complete self-assessments and creative exercises that provide unique insights into your leadership strengths and opportunities for growth.

- A transformative experience: Move through the 12 stages of the Hero’s Journey, exploring the archetypes that shape your leadership story. Reflect on your purpose, your values, your vision, and your legacy.

- A community of peers: Share your journey with others, learning from their stories and contributing your own. Build relationships, foster trust, and create a network of support and inspiration.

- A sanctuary for reflection and renewal: Immerse yourself in the beauty and power of Rodin’s art, using it as a catalyst for self-discovery, creativity, and transformation.

VII. The Role of Peter de Kuster: Guide, Storyteller, Innovator

Peter de Kuster is your guide on this journey. As the founder of The Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey projects, he has dedicated his life to helping creative professionals and leaders create careers and lives based on the stories most integral to their values, traits, skills, and experiences. His approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, honed over more than 20 years of working with clients on a wide range of creative business challenges.

Peter is the author of the acclaimed Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey book series, and holds MBAs in Marketing and Financial Economics, as well as degrees in Sociology and Communication Sciences. His work is grounded in the belief that “everyone can lead by using stories to effect change”-and that the right story at the right time can make an audience “stunningly vulnerable to a new idea”.

Peter’s leadership journeys are not lectures, but immersive experiences. They are designed to be interactive, reflective, and deeply personal. You will be challenged to learn-by-doing, to come up with new ideas and solutions, to reflect on your own story, and to apply what you learn in practice.

VIII. The Structure of the Journey: From Ordinary World to Return with the Elixir

The journey is structured around the 12 stages of the Hero’s Journey, each illustrated by a masterpiece from Rodin’s oeuvre. For each stage, you will find:

- A selected artwork: A masterpiece by Auguste Rodin, chosen to embody the archetype and stage of the journey.

- An in-depth exploration of the artwork from the Hero’s Journey perspective, connecting art, story, and leadership.

- Reflective questions: Prompts to help you explore your own leadership story, challenges, and opportunities.

- Creative exercises: Activities to deepen your self-awareness, foster innovation, and translate insight into action.

This structure is designed to guide you through the journey of transformation-from the comfort of the ordinary world, through the trials and tests of the unknown, to the return home with new wisdom, vision, and power.

IX. The Promise of Transformation: What You Will Gain

By engaging with this journey, you will:

- Discover your leadership story: Gain clarity about your purpose, values, and vision. Understand the archetypes that shape your behavior and choices.

- Unlock your creative potential: Learn how to use storytelling to spark innovation, foster collaboration, and overcome resistance.

- Build trust and connection: Develop the skills to communicate authentically, build relationships, and inspire others.

- Navigate change with confidence: Gain tools and frameworks for leading through uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

- Create a legacy: Articulate the impact you want to have, the story you want to tell, and the difference you want to make.

As Peter de Kuster writes, “The journey is not just about art or leadership-it’s about choosing to live heroically, to embrace change, and to create your own legend. The story you tell yourself shapes your reality. Will you choose to be the hero or heroine of your own journey?”

X. The Power of Art: Why Rodin, Why Now

Art has the power to move us, to challenge us, to awaken us to new possibilities. Rodin’s sculptures are not just objects of beauty; they are invitations to reflect, to question, to imagine, and to grow. In the Musée Rodin, surrounded by the masterpieces of a creative genius, you are invited to step out of your routine, to see yourself and your story with new eyes, and to reconnect with what matters most.

As you move through the 12 stages of the journey, let the art be your mirror, your guide, your inspiration. Let it challenge your assumptions, awaken your creativity, and open your heart to new ways of being and leading.

XI. The Invitation: Your Story Awaits

This journey is an invitation-to reflection, to creativity, to transformation. It is an opportunity to step into your own story, to become the leader you were meant to be, and to create a legacy that endures.

Below you’ll find a leadership journey through the Musée Rodin, following Peter de Kuster’s Hero’s Journey story model with 12 archetypes. For each stage, I’ve selected a masterpiece by Auguste Rodin, provided the artist’s name, and offered a 500-word explanation from the Hero’s Journey perspective-including questions and exercises to help leaders explore their own story.

Are you ready to begin? The journey awaits. Your story is yours to tell.

The Leadership Journey in Musée Rodin: 12 Archetypes, 12 Masterpieces

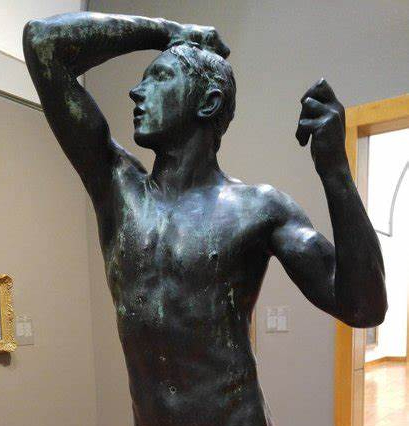

The Ordinary World – “The Age of Bronze”

Artist: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Introduction: The Hero’s Journey Begins at Home

Every great journey starts in the ordinary world-a place of comfort, familiarity, and routine. In Hero’s Journey, this is the stage where the protagonist’s life is in balance, but often tinged with a sense of restlessness or incompleteness. It is the world you know: your daily habits, your relationships, your leadership style, and the status quo of your organization or community. The ordinary world is not just a backdrop; it is the soil from which the seeds of adventure and transformation will grow

Auguste Rodin’s The Age of Bronze stands as a powerful metaphor for this stage. Completed in 1876 and exhibited to scandal and acclaim in 1877, this life-sized sculpture of a young man is suspended between rest and awakening, between innocence and experience, between the world as it is and the world as it could be. To stand before The Age of Bronze is to stand on the threshold of your own story-aware of what is, and what might be.

The Sculpture: Awakening in Bronze

Rodin’s The Age of Bronze was revolutionary for its time. Unlike the heroic, idealized figures of classical and academic art, Rodin’s young man is startlingly real. Fashioned after the 22-year-old Belgian soldier Auguste Neyt, the figure’s body is rendered with meticulous naturalism: every muscle, vein, and contour is observed from life. The right leg is bent in a classical contrapposto pose, echoing ancient Greek sculpture, but the overall effect is ambiguous-neither fully at rest nor fully in motion.

The figure’s eyes are closed, his mouth slightly open. His right hand rests on his head, while the left is raised, as if he is waking from a deep sleep or perhaps shielding himself from something unseen. Originally, the left hand held a spear, but Rodin removed it, stripping the work of any clear narrative or historical reference. Instead, he left us with a universal image: a human being at the moment of awakening, caught between the past and the future, between innocence and knowledge.

The title itself is layered with meaning. The Age of Bronze refers to a pivotal era in human history, when our ancestors first learned to forge tools and weapons from bronze, marking the dawn of civilization and human ingenuity. Yet, the original titles-The Vanquished, The Wounded Soldier, The Awakening Man-hint at vulnerability, struggle, and the possibility of renewal. Rodin himself encouraged multiple interpretations, saying, “There are at least four figures in it”.

The Ordinary World: A Place of Comfort and Constraint

In the context of the Hero’s Journey, the ordinary world is a place of both comfort and constraint. It is the realm of the “innocent” archetype, where we feel safe, competent, and in control. But it is also a world bounded by routines, assumptions, and unexamined beliefs. For leaders, this might be the familiar rhythms of your team, the culture of your organization, or the habits that define your personal and professional life.

Rodin’s sculpture captures this tension perfectly. The young man is at ease, yet there is a subtle dynamism in his pose-a sense that he is on the verge of movement, of awakening to something new. The contrapposto stance, borrowed from ancient art, suggests both balance and potential energy. The hands, framing the head, draw our attention to the center of thought and feeling, hinting at an internal struggle or realization.

This is the essence of the ordinary world: a place where you know the rules, but where you may also feel a quiet longing for something more. As John Sadowsky notes, “The hero is comfortable in the ‘ordinary world’, but at the same time uneasy, as if he does not completely ‘fit’ there in some way. His world is familiar and easy, but something is missing in the hero’s life, whether or not he can define it”.

The Scandal of Realism: Disrupting the Ordinary

When Rodin first exhibited The Age of Bronze, it caused a sensation. Critics accused him of cheating-of casting the figure directly from the model, so lifelike was the result. What they failed to see was that Rodin was challenging the very conventions of art and storytelling. By rejecting mythological or historical references, he invited viewers to see themselves in the figure-to recognize their own moment of awakening, their own ordinary world.

For leaders, this is a crucial insight. The ordinary world is not static; it is always on the edge of change. The very act of seeing yourself clearly-of recognizing your strengths, your routines, your blind spots-is itself a radical act. It is the first step toward transformation, but it is also a moment fraught with uncertainty and vulnerability.

Rodin’s decision to remove the spear and leave the figure ambiguous is a gift to us. It allows each viewer to project their own story onto the sculpture. Is the young man awakening to joy or to suffering? Is he vanquished or victorious? Is he about to rise, or has he just fallen? The ordinary world is full of such questions, and it is in asking them that the journey begins.

The Leader as Hero: Recognizing Your Ordinary World

In leadership, the ordinary world is the context in which you operate every day. It is the sum of your habits, your relationships, your organizational culture, and your personal story. It is where you feel most at home-and where you may also feel most constrained.

The Hero’s Journey teaches us that every leader is first a hero in their own life. Your ordinary world is not just a stage; it is the foundation of your character and your quest. It is where you learn the values, skills, and beliefs that will shape your adventure. But it is also where you encounter the limits of your current story-the places where you feel stuck, restless, or unfulfilled.

Rodin’s The Age of Bronze invites you to pause and reflect on your own awakening. The figure’s closed eyes and half-open mouth suggest a moment of introspection, of listening to the quiet voice within that calls you to something greater. The ambiguity of the pose mirrors the ambiguity of your own journey: you may not know exactly what lies ahead, but you sense that change is coming.

Reflection: Questions for Leaders

- What is your ordinary world as a leader?

Describe the routines, relationships, and environments that define your daily life. Where do you feel most comfortable? Where do you feel most constrained? - What strengths do you bring to your current context?

List the skills, values, and experiences that have served you well so far. How have they shaped your leadership? - Where do you sense restlessness or longing?

Is there an area of your life or work where you feel called to something more? What is missing, even if you cannot yet name it? - What are the unexamined assumptions or habits that define your ordinary world?

Are there beliefs or routines that you take for granted? How might they be limiting your growth?

Exercise: Mapping Your Ordinary World

- Draw a map of your ordinary world.

On a blank sheet of paper, sketch the key elements of your daily life: your work, your relationships, your routines, your sources of comfort and stress. Label each area with a word or phrase that captures its significance. - Identify the boundaries.

Mark the edges of your map-the places where your comfort zone ends and the unknown begins. Where do you feel resistance to change? Where do you sense opportunity? - Reflect on your awakening.

Like the figure in The Age of Bronze, consider what it would mean to awaken in your own life. What would you need to see, feel, or understand in order to move forward? - Write a journal entry from the perspective of the figure in the sculpture.

Imagine you are standing at the threshold of awakening. What are you thinking? What are you feeling? What do you hope for, and what do you fear?

The Universal Moment: The Ordinary World in All Our Stories

Rodin’s The Age of Bronze is not just a work of art; it is a mirror for our own experience. The ordinary world is universal-every leader, every hero, every human being begins here. It is the place where we learn, grow, and prepare for the unknown. It is also the place we must leave behind if we are to answer the call to adventure.

The ambiguity of the sculpture is its genius. By refusing to tell us exactly what the figure is experiencing, Rodin invites us to find our own meaning. Is this the moment before action, or after defeat? Is it the end of one story, or the beginning of another? The answer, of course, is both. The ordinary world is always both an ending and a beginning-a place of comfort, and a place of longing.

Conclusion: The Ordinary World as the Seed of Transformation

As you stand before The Age of Bronze, take a moment to honor your own ordinary world. Recognize the strengths and comforts that have brought you this far. Acknowledge the routines and assumptions that keep you safe, but also the restlessness that calls you to something more.

The Hero’s Journey teaches us that transformation begins not with a leap, but with an awakening-a moment of seeing ourselves clearly, of listening to the quiet voice within, of recognizing that the world as it is does not have to be the world as it will be. Rodin’s sculpture captures this moment with unparalleled power: a young man, caught between sleep and waking, between innocence and experience, between the past and the future.

As a leader, your ordinary world is the foundation of your story. It is where you prepare for the journey ahead, where you gather your strengths and confront your limitations. It is the place you must leave, but also the place you will one day return to, transformed.

The journey begins here-with an awakening, a question, a longing for something more. The Age of Bronze is your invitation to step into your own story, to become the hero of your own life, and to create a new legend for yourself and those you lead.

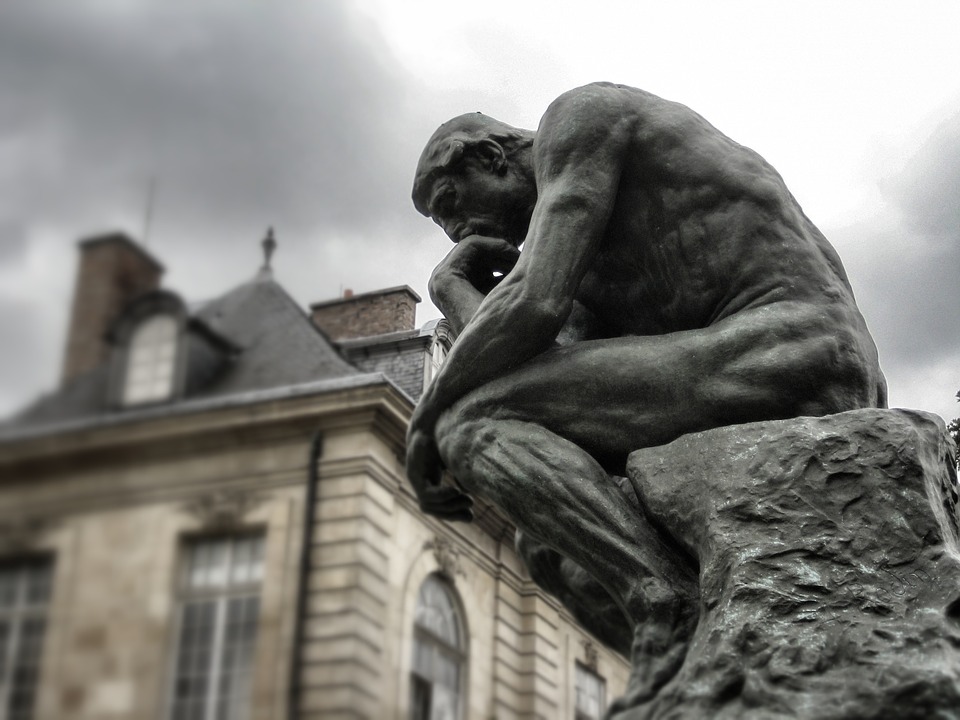

2. The Call to Adventure – “The Thinker”

Introduction: The Disruption of the Ordinary

In every leader’s life, there comes a moment when the familiar world-the comfort of routine, the safety of established roles-begins to feel too small. This is the “call to adventure,” the second stage in the Hero’s Journey. It is the moment when you sense there is more to your story, when a challenge, a crisis, or a deep longing disrupts the ordinary and beckons you toward growth.

Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker is the embodiment of this moment. Originally conceived as Dante, the poet contemplating the fates of souls in The Divine Comedy and the torments depicted in The Gates of Hell, The Thinker has transcended its origins to become a universal symbol of contemplation, decision, and the search for meaning. It is the image of a human being on the threshold of transformation, wrestling with the questions that define not only their destiny but the very nature of existence.

The Sculpture: Anatomy of a Question

The Thinker is a monumental bronze figure, heroic in size and presence. Seated on a rock, the nude male form leans forward, right elbow on left thigh, chin resting on his hand in a gesture of profound thought. Every muscle is tensed, every sinew alive with energy, yet the figure is utterly still-a paradox of physical power and mental absorption.

Rodin’s choice to depict the act of thinking as muscular, even athletic, was revolutionary. As the Philadelphia Museum of Art notes, “By choosing to depict The Thinker as a strong, athletic figure, Rodin conveyed that the act of thinking is a powerful exercise”. The body is not relaxed but coiled, as if the very act of contemplation is a struggle, a battle between the known and the unknown.

Originally, this figure was meant to be Dante, observing the circles of Hell from above the Gates. But as Rodin’s vision evolved, The Thinker became less a portrait of a specific poet and more an archetype-a stand-in for every artist, philosopher, scientist, and leader who has ever dared to question, to imagine, to create.

The Seeker’s Awakening: The Call in Leadership

For leaders, the call to adventure is rarely clear-cut. It may come as a whisper-a nagging sense that something is missing, a quiet dissatisfaction with the status quo. Or it may arrive as a shout-a new project, a sudden crisis, a personal or organizational upheaval. What unites these experiences is the awakening of the “seeker” archetype: the part of you that yearns for growth, that is willing to question assumptions and imagine a different future.

Standing before The Thinker, you are invited into this moment of awakening. The sculpture’s intense focus, the tension in its muscles, the furrowed brow and compressed lips-all speak to the inner struggle of the seeker. This is not idle daydreaming; it is the hard, sometimes painful work of confronting reality and daring to ask, “What if?”

Rodin’s own artistic journey mirrors this stage. Rejected by the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, Rodin developed a freer, more emotional style that would become his signature6. The Thinker is a product of this spirit-unbound by tradition, open to new possibilities.

The Universal Struggle: Contemplation as Courage

The Thinker is universally recognized as a symbol of philosophy, introspection, and the uniquely human capacity for self-examination. But it is also a symbol of struggle. The figure’s posture is not one of ease but of wrestling-with ideas, with doubts, with the weight of responsibility.

In leadership, this struggle is familiar. The call to adventure is not just about action; it is about questioning your own beliefs, your organization’s culture, your industry’s norms. It is about facing the discomfort that comes with growth-the fear of failure, the risk of change, the uncertainty of the unknown.

The Thinker’s gaze is directed downward, as if looking into the abyss of possibility and consequence. His body is drawn inward, coiled around the question at hand. This is the moment when you, as a leader, must decide: Will you heed the call? Will you step into the unknown, or retreat into the safety of the ordinary world?

The Evolution of Meaning: From Dante to Everyman

When The Thinker was first exhibited, it was named The Poet, and closely associated with Dante. But over time, as Rodin enlarged and exhibited the sculpture independently, it became clear that its meaning was far broader. The figure became a stand-in for all who think deeply-for artists, writers, scientists, and ordinary people alike.

This evolution mirrors the journey of every leader. The call to adventure may begin with a specific challenge-a new market, a disruptive technology, a personal crossroads-but it quickly becomes a universal question: What am I meant to do? What legacy will I leave? How will I respond to the needs of my time?

Rodin himself identified deeply with The Thinker. A version of the sculpture overlooks his own tomb, a testament to the centrality of contemplation and courage in his life and work. For leaders, this is a reminder that the call to adventure is not a one-time event, but a recurring invitation to grow, to question, to create.

The Emotional Landscape: Wrestling with Doubt

The physical intensity of The Thinker reflects the emotional intensity of this stage. The act of thinking is not passive; it is an active engagement with possibility and risk. The figure’s clenched fist, gripping toes, and furrowed brow all suggest the pain and difficulty of true contemplation.

For leaders, this is often a time of doubt and anxiety. The questions that arise may be uncomfortable, even frightening. What if I fail? What if I am not enough? What if the world I know is changing faster than I can adapt?

Yet, as Rodin’s sculpture reminds us, these emotions are not signs of weakness, but of courage. To think deeply, to question honestly, is to open yourself to transformation. It is to stand at the threshold of the unknown, willing to risk comfort for the sake of growth.

The Thinker as a Leadership Archetype

In the Hero’s Journey, the call to adventure is the moment when the protagonist’s ordinary world is disrupted and a new path beckons. In leadership, this is the moment when you realize that what has brought you here will not take you further. The “seeker” archetype awakens, and you begin to look beyond the familiar for new answers.

The Thinker is the perfect embodiment of this archetype. The sculpture’s heroic size and muscular form suggest that thinking-true, creative, courageous thinking-is itself a heroic act. It requires strength, discipline, and the willingness to face discomfort.

As you contemplate The Thinker, ask yourself: What is calling me to grow? Where do I feel a sense of longing or dissatisfaction? What question keeps returning to my mind, demanding attention?

The Leadership Questions: Embracing the Call

- What is calling you to change or grow in your leadership?

Is it a new opportunity, a challenge, a crisis, or a quiet longing for something more? - Where do you feel a sense of longing or dissatisfaction?

Are there areas of your work or life where you feel restless, unfulfilled, or out of alignment with your values? - What question keeps returning to your mind?

Is there a persistent thought or concern that you have been avoiding? What would it mean to confront it honestly?

Exercise: Sitting with the Question

- Write down the question that most often occupies your thoughts about your leadership journey.

It might be: “Am I making a difference?” “Is this the right path?” “What is my true purpose?” - Sit with it in silence for a few minutes.

Close your eyes, breathe deeply, and allow the question to fill your awareness. Notice any emotions that arise-fear, excitement, confusion, hope. - Reflect on what you discover.

Write about the feelings, memories, or ideas that come up. What is your heart telling you? What is your mind resisting?

The Power of Imagination: Creating the Future

Rodin believed that thinking was not just about analysis, but about imagination-the ability to envision new possibilities, to create worlds that do not yet exist. The Thinker is not only contemplating the present, but dreaming of the future.

For leaders, this is a crucial insight. The call to adventure is not just a summons to action, but an invitation to imagine what could be. It is the moment when you dare to see beyond the limits of your current reality, to envision a new story for yourself, your team, your organization.

The act of thinking, as Rodin presents it, is generative. It is the source of innovation, creativity, and transformation. To heed the call to adventure is to become a creator of the future, not just a manager of the present.

The Thinker in Context: A Global Icon

Today, The Thinker is one of the most recognized sculptures in the world, with versions in museums and public spaces across the globe. Its image is used to symbolize philosophy, creativity, and the power of the human mind.

But its true power lies in its invitation to each of us: to pause, to question, to imagine. In a world that often values speed and action above all, The Thinker reminds us that the most important journeys begin with a question, a moment of stillness, a willingness to listen to the call within.

Conclusion: Answering the Call

The call to adventure is the beginning of every great story-yours included. It is the moment when you awaken to the possibility of more, when you dare to question the world as it is and imagine the world as it could be.

Rodin’s The Thinker stands as a monument to this moment-a reminder that true leadership begins not with answers, but with questions. To be a leader is to be a seeker, to sit with uncertainty, to wrestle with doubt, and to dream of what might be.

As you stand before The Thinker, let yourself feel the weight of your own questions. Honor the courage it takes to think deeply, to imagine boldly, to answer the call to adventure. The journey ahead will not be easy, but it will be yours-and it begins with a single, powerful question.

3. Refusal of the Call – “The Gates of Hell”

Artist: Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Introduction: Standing Before the Threshold

In every great story, after the hero receives the call to adventure, there comes a moment of hesitation. The world as it was-safe, familiar, and predictable-now stands in contrast to the unknown that beckons. This is the stage of Refusal of the Call, a universal moment of fear, doubt, and resistance. In the Hero’s Journey, this is where the protagonist wavers, questioning whether the risks of change are worth the potential rewards. For leaders, it is the crossroads where vision collides with vulnerability, and where the first true test of character emerges: Will you step forward, or will you turn away?

No artwork captures the agony and complexity of this moment quite like Auguste Rodin’s monumental masterpiece, The Gates of Hell. Conceived in 1880 and worked on for nearly four decades, this six-meter-high bronze portal teems with over 180 writhing figures, each locked in their own struggle, each a fragment of torment, longing, or lost hope. Inspired by Dante’s Inferno, Rodin’s vision ultimately transcended its literary source, becoming a universal meditation on human suffering, resistance, and the possibility of transformation.

The Artwork: Chaos, Resistance, and the Human Condition

The Gates of Hell was originally commissioned as the entrance to a Decorative Arts Museum in Paris-a museum that was never built. Yet Rodin’s commitment to the project never wavered. For 37 years, he added, removed, and reimagined the figures on the doors, using the commission as a laboratory for his most radical ideas. Many of his most famous sculptures-The Thinker, The Kiss, The Three Shades-began as details within these gates before being cast as independent works.

Standing before The Gates of Hell, one is overwhelmed by the sheer density of human emotion. The figures are not neatly arranged or compartmentalized, as in the doors of Ghiberti’s Renaissance Gates of Paradise (which inspired Rodin’s early sketches). Instead, they tumble, twist, and writhe in a chaotic, almost gravitationally unbound space. There is no clear narrative, no single story; rather, the gates present a tapestry of suffering, desire, and existential anguish.

Rodin’s technical innovation is evident everywhere. He abandoned the idealized forms of Greek and Baroque sculpture in favor of expressive distortion. Bodies are elongated, hands and feet exaggerated, faces contorted in agony or ecstasy. The surface ripples with the marks of Rodin’s own hands, as if the bronze itself is alive, still in the process of becoming. This is not a static monument, but a living, breathing vision of the human soul in crisis.

Dante’s Inferno and the Orphan Archetype

Rodin’s inspiration came from Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, the first part of The Divine Comedy. In Dante’s vision, Hell is a place of punishment, but also of profound psychological insight. Each circle of Hell represents a different form of human failing-lust, gluttony, greed, wrath, and so on-but also a different kind of suffering, a different kind of refusal to change.

For Rodin, the gates became a metaphor for the orphan archetype in the Hero’s Journey. The orphan is the part of us that feels abandoned, alone, and powerless in the face of overwhelming odds. In leadership, this is the moment when you feel isolated by your vision, unsure of your abilities, and tempted to retreat to the safety of the known. The figures on the gates are caught in this psychological “hell”-not because they are evil, but because they are unable or unwilling to move forward.

Rodin’s gates are peopled not just by Dante’s sinners, but by universal figures of humanity: lovers, mothers, children, the fallen, the yearning, the lost. The agony depicted is not just physical, but existential-the agony of indecision, of longing for change but fearing its consequences. The gates become a mirror for our own moments of refusal, our own struggles with fear and self-doubt.

The Psychological Hell of Indecision

What makes The Gates of Hell so powerful is not just its scale or technical brilliance, but its psychological depth. Rodin was a Symbolist at heart, seeking to penetrate the innermost essence of being3. The gates are not just a depiction of Dante’s Hell; they are a map of the human psyche at the moment of crisis.

For leaders, this stage is painfully familiar. After the excitement of the call to adventure, reality sets in. Doubts arise: Am I ready for this? What if I fail? What will others think? The risks seem overwhelming, the path unclear. The voices of caution-internal and external-grow louder: “You can’t do this.” “It’s too dangerous.” “Better to stay where you are.”

The figures on Rodin’s gates embody this paralysis. Some reach upward, yearning for escape; others collapse inward, consumed by despair. There is movement, but no progress-struggle without resolution. This is the psychological “hell” of indecision, where every option seems fraught with peril, and the cost of change appears too high.

Yet, as in all great art, there is more here than meets the eye. The very act of struggle is itself a form of resistance-a refusal to surrender entirely. The figures may be trapped, but they have not given up. Within the gates are the seeds of transformation, the possibility that suffering can lead to insight, and that the refusal of the call is itself a necessary stage on the path to growth.

Seeds of Transformation: Struggle as Preparation

Rodin’s genius was to recognize that resistance is not the end of the story, but a vital part of it. The refusal of the call is not a failure, but a stage of preparation. It is in wrestling with our doubts, fears, and limitations that we begin to clarify what truly matters to us. The agony of the figures on the gates is not just punishment; it is the crucible in which the self is tested and refined.

For leaders, this is a crucial lesson. The moments when you feel most alone, most uncertain, are often the moments when you are closest to breakthrough. The voices that tell you to stay safe, to avoid risk, are not your enemies-they are your teachers. They force you to examine your motives, to confront your fears, and to decide whether your vision is worth the cost.

Rodin’s own creative process mirrors this dynamic. He worked on the gates for nearly forty years, never satisfied, always revising, adding, subtracting, reimagining. The project became a metaphor for his own struggles with doubt, perfectionism, and the demands of his art. Yet out of this chaos came some of the most powerful sculptures of the modern era-proof that struggle, far from being an obstacle, is often the source of our greatest achievements.

The Gates as a Metaphor for Leadership

In the context of leadership, The Gates of Hell can be seen as the threshold between the world as it is and the world as it could be. To stand before the gates is to confront the full weight of your responsibilities, your fears, and your hopes. It is to acknowledge the cost of change, the pain of letting go, and the uncertainty of what lies ahead.

The gates are not just an obstacle; they are an invitation. They ask: Are you willing to face your own hell-the doubts, the criticisms, the failures-so that you can move forward? Are you willing to risk comfort for the sake of growth? Are you willing to let go of the familiar, even if it means stepping into the unknown?

Rodin’s masterpiece reminds us that leadership is not about avoiding suffering, but about finding meaning in it. The figures on the gates are not passive victims; they are active participants in their own stories. Their agony is real, but so is their longing for something more. The gates become a symbol of the leader’s journey-a journey that begins not with certainty, but with the courage to face uncertainty.

Artistic Innovation: Breaking the Mold

Rodin’s approach to The Gates of Hell was as radical as its subject matter. He rejected the idealized, compartmentalized structure of earlier monumental doors, such as Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise. Instead, he created a swirling, organic composition where figures merge, separate, and reappear in different forms7. The boundaries between individual stories dissolve, creating a sense of collective struggle and shared humanity.

Rodin also broke with tradition in his technique. He preferred to model in clay or plaster, allowing for constant revision and experimentation. The tactile quality of the surfaces-the fingerprints, the rough edges, the visible seams-conveys a sense of immediacy and emotional intensity. The gates are not polished or finished; they are alive, in process, always becoming.

This artistic innovation mirrors the psychological journey of the leader. The refusal of the call is not a tidy, linear process; it is messy, chaotic, and full of contradictions. Progress is not measured by outward success, but by the willingness to stay engaged with the struggle, to keep asking questions, to keep moving forward even when the outcome is uncertain.

Universal Emotions: Suffering, Longing, and Hope

One of the most remarkable aspects of The Gates of Hell is its ability to evoke universal human emotions. The figures on the gates are not just sinners or victims; they are us. Their suffering is our suffering, their longing is our longing, their hope is our hope.

Rodin’s decision to remove specific narrative references from many of the figures allows viewers to project their own stories onto the gates. The agony of a mother losing her child, the despair of a betrayed lover, the yearning of a soul for redemption-all are present here, rendered with a rawness and honesty that transcends time and culture.

For leaders, this universality is both a comfort and a challenge. It reminds us that we are not alone in our struggles, that the refusal of the call is a shared human experience. But it also challenges us to move beyond self-pity or resignation, to recognize that within our suffering lies the possibility of growth and transformation.

The Gates in Rodin’s Career: A Life’s Work

The Gates of Hell was never cast in bronze during Rodin’s lifetime. The original plaster model remained in his studio, a constant presence and a source of inspiration for other works. After his death, the first bronze casts were made, and today the gates can be seen in several locations around the world, including the Musée Rodin in Paris and the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia.

For Rodin, the gates were more than a commission; they were a lifelong obsession, a canvas on which he worked out his deepest fears, hopes, and artistic ambitions. The project’s unfinished nature is itself a testament to the ongoing nature of the human journey. There is always more to struggle with, more to learn, more to become.

The Hero’s Journey Perspective: Refusal as a Crucible

In the Hero’s Journey, the Refusal of the Call is not a sign of weakness, but a necessary crucible. It is the moment when the hero confronts the full cost of the journey ahead and must decide whether to proceed. The refusal may be brief or prolonged, conscious or unconscious, but it is always a test of resolve.

For leaders, this stage is where true commitment is forged. It is easy to say yes to adventure when it is only an idea; it is much harder when the risks become real. The refusal is the fire in which your motives, values, and vision are tested. Will you move forward, or will you turn back?

Rodin’s Gates of Hell offers a powerful metaphor for this process. The gates are both barrier and threshold, both prison and passage. To pass through them is to leave behind the safety of the known and to step into the chaos of creation. The agony of the figures is real, but so is their longing for release.

Questions for Reflection

- What fears hold you back from embracing change?

List the specific anxieties, doubts, or risks that make you hesitate. Are they rooted in past experiences, in external pressures, or in your own self-image? - Who or what tells you “you can’t”?

Identify the voices-internal or external-that discourage you from moving forward. Are they protective, critical, or simply afraid? - What is the cost of staying where you are?

Consider not just the comfort of the status quo, but the opportunities lost, the growth foregone, the dreams deferred.

Exercise: Facing the Gates

- List your top three fears about stepping into the unknown.

Be honest and specific. Are you afraid of failure, of judgment, of losing control, of disappointing others? - For each fear, write a possible outcome if you faced it.

What is the worst that could happen? What is the best? What is most likely? - What might you gain?

Reflect on the potential rewards-personal growth, new opportunities, deeper relationships, greater impact. - Imagine yourself as one of the figures on the gates.

What is your posture? Are you reaching upward, collapsing inward, yearning for escape? What would it take to move?

Conclusion: The Gates as Passage, Not Prison

Standing before The Gates of Hell, you are confronted with the full complexity of the refusal stage. The agony, the longing, the chaos-all are real, all are necessary. But the gates are not just a prison; they are a passage. To refuse the call is not to fail, but to prepare. It is to wrestle with your fears, to clarify your motives, to test your resolve.

Rodin’s masterpiece reminds us that the journey of transformation is not linear or easy. It is messy, painful, and full of uncertainty. But within the struggle lies the possibility of growth, and within the gates lies the promise of a new beginning.

As a leader, your refusal is not the end of your story. It is the crucible in which your true self is forged. The gates may seem insurmountable, but they are also the threshold to your greatest adventure.

4. Meeting the Mentor – “Monument to Balzac”

Introduction: The Mentor’s Arrival on the Path of the Hero

In the journey of transformation, after the initial call and the deep wrestling with doubt and resistance, comes a pivotal moment: the appearance of the mentor. In the Hero’s Journey, this is the stage where the protagonist receives guidance, wisdom, or a new perspective-often just when it is needed most. The mentor does not always provide answers, but they offer something deeper: the courage to continue, the tools to grow, and the reminder that the hero is not alone.

In the world of art, few sculptures embody the mentor archetype as powerfully as Auguste Rodin’s Monument to Balzac. This monumental work, completed after seven years of obsessive study and creative struggle, stands not only as a tribute to the great French novelist Honoré de Balzac but as a symbol of creative mastery, perseverance, and the mysterious alchemy of mentorship itself.

To stand before Rodin’s Balzac is to encounter the very essence of the mentor: enigmatic, formidable, and deeply human. The sculpture’s rough, unfinished surface and imposing presence challenge us to reconsider what mentorship means. Is it about perfection? Or is it about authenticity, courage, and the willingness to see-and evoke-the greatness in others?

The Commission and the Struggle: Rodin’s Own Heroic Quest

The story of the Monument to Balzac begins in 1891, when Rodin was commissioned by the Société des Gens de Lettres-a literary society founded by Balzac himself-to create a monument to the writer for the Palais Royal in Paris. Balzac was a towering figure in French literature, the author of La Comédie humaine, a sprawling collection of nearly a hundred stories and novels that captured the complexity of contemporary French life. The society wanted a public statue that would honor Balzac’s physical likeness and his literary achievement.

Rodin, however, had a different vision. He became obsessed with capturing not just the outward appearance of Balzac, but his creative spirit, his inner fire, and his mythic presence. For seven years, Rodin immersed himself in Balzac’s world: he read everything written about the author, gathered every known image, and traveled to Balzac’s native Touraine to absorb the landscape that had shaped him. He even commissioned Balzac’s former tailor to recreate the writer’s famous monk’s robe, which Balzac wore during his late-night writing marathons.

Rodin’s process was anything but straightforward. He produced more than fifty studies, ranging from nude, muscular figures in the stance of a wrestler to heavily cloaked, almost abstract forms. He experimented with exaggerated features-a bullish neck, a lion-like mane, a sensual mouth, and fiery eyes. He sketched, modeled, and revised endlessly, searching not for a physical likeness but for a psychological truth that would capture the essence of Balzac’s genius.

This obsessive quest mirrors the journey of every hero who seeks a mentor. The mentor is not always easy to find, and their wisdom is rarely handed over without effort. Often, the mentor’s greatest gift is not a solution, but a challenge-a call to dig deeper, to question assumptions, and to discover one’s own strength.

The Mentor as Enigma: The Final Monument

When Rodin finally exhibited the plaster model of the monument at the Salon of 1898, it was met with ridicule and controversy. Critics called it a “snowman,” a “seal,” a “block of salt caught in a shower,” and a “crude sketch” in which they did not recognize Balzac. The commissioners rejected it, and Rodin, wounded by the criticism, withdrew the monument from public view for the rest of his life.

It was not until 1939, more than two decades after Rodin’s death, that the plaster was finally cast in bronze and installed in Paris at the intersection of Boulevards Montparnasse and Raspail. By then, the art world had caught up with Rodin’s vision, and the monument was hailed as a revolutionary work-perhaps the first truly modern sculpture.

What makes the Monument to Balzac so powerful, and so challenging, is its refusal to offer easy answers. Balzac is not depicted in a familiar pose, with pen or book in hand. Instead, he is transformed into a dense, formidable monolith, his body enveloped in a shapeless, oversized dressing gown. His gaze is fixed toward the horizon, his presence both grounded and transcendent. The sculpture is less a portrait than an evocation-a powerful symbol of creative mastery, perseverance, and the mystery at the heart of mentorship.

The Mentor’s Essence: Authenticity Over Perfection

Rodin’s approach to the Balzac monument broke entirely with the sculptural traditions of the past. Instead of presenting an idealized, polished image, Rodin embraced roughness, ambiguity, and expressive force. The surface of the sculpture is deliberately unfinished, alive with the marks of the artist’s hand. The robe is more like a shroud or a cocoon, hiding as much as it reveals. The face is not a photographic likeness, but an amalgam of features, distilled and exaggerated to capture Balzac’s inner vitality.

This radical departure from convention was not just an artistic choice; it was a philosophical statement. Rodin believed that true greatness could not be captured by superficial accuracy. As he explained, “A man celebrated for his heart and mind should not be [represented by] his body”. Instead, he sought to evoke the spirit, the creative force, the intangible qualities that make a person a mentor, a guide, a legend.

For leaders, this is a profound lesson. The mentor is not the one who has all the answers or who embodies perfection. The mentor is the one who is authentic, who has struggled, who is willing to share their journey-their failures as well as their triumphs. The mentor’s power lies not in their invulnerability, but in their humanity.

The Mentor’s Role: Encouragement, Challenge, and Reflection

In the Hero’s Journey, the mentor appears at a crucial moment-often just as the hero is wavering, unsure, or afraid. The mentor offers wisdom, encouragement, or a new perspective. Sometimes the mentor is a person: a teacher, a coach, a friend, or a parent. Sometimes the mentor is a book, a work of art, or even an inner voice that reminds us of our own strength.

Rodin’s Balzac stands as a symbol of this role. His presence is both grounding and inspiring. He does not offer easy comfort; instead, he challenges us to see ourselves more clearly, to embrace our own creative power, and to persevere in the face of criticism or failure.

The rough, unfinished surface of the sculpture is a reminder that mentorship is not about handing down polished truths. It is about sharing the ongoing process of becoming, about modeling the courage to be imperfect, to risk rejection, and to keep growing. The mentor’s greatest gift is not a map, but a mirror-a way of seeing ourselves and our journey with new eyes.

The Mentor’s Challenge: Facing Criticism and Rejection

The story of the Balzac monument is also a story of resilience in the face of criticism and rejection. Rodin poured his heart and soul into the project, only to have it dismissed by the very people who had commissioned it. The pain of this rejection was profound, and for a time, Rodin withdrew from public life.

Yet, in the long run, the monument’s vindication speaks to the enduring power of authentic vision. The mentor is not always recognized or appreciated in their own time. Their wisdom may be misunderstood, their methods questioned, their presence resisted. But the true mentor persists-not for the sake of approval, but for the sake of truth.

For leaders, this is a crucial lesson. The mentors who shape us are often those who challenge us, who refuse to let us settle for easy answers, who push us to grow beyond our comfort zones. Their guidance may not always be welcome, but it is always valuable.

The Mentor Within: Seeking Guidance in Unexpected Places

Not every mentor is a person. Sometimes, the mentor appears as an experience, a work of art, a moment of insight, or an inner voice that calls us to greater authenticity. Rodin’s Balzac, with its enigmatic presence and refusal to conform, invites us to seek mentorship in unexpected places.

For leaders, this means being open to guidance from all sources. It means reading widely, listening deeply, and being willing to learn from failure as well as success. It means recognizing that the mentor’s role is not to provide a script, but to awaken the hero’s own capacity for growth and transformation.

The mentor may offer comfort, but more often, they offer challenge. They remind us that the journey is not about avoiding difficulty, but about embracing it as the crucible in which character is forged.

The Mentor’s Legacy: Inspiring Future Generations

Today, Rodin’s Balzac is recognized as one of the greatest sculptures of the nineteenth century-perhaps, as Kenneth Clark suggested, “the greatest piece of sculpture of the nineteenth century-perhaps, indeed, since Michelangelo”. Its influence can be seen in the work of countless artists, writers, and thinkers who followed.

But its true legacy lies in its power to inspire. The monument stands as a beacon for all who seek to create, to lead, to mentor. It reminds us that greatness is not about conformity, but about the courage to be oneself, to follow one’s own vision, and to help others do the same.

For leaders, the mentor’s legacy is measured not in accolades or monuments, but in the lives they touch, the wisdom they share, and the courage they inspire in others.

Reflection: Questions for Leaders

- Who has been a mentor in your life?

Think of the people, books, or experiences that have shaped your journey. What qualities made them mentors for you? - What is the most valuable lesson you’ve learned from them?

Reflect on the wisdom, encouragement, or challenge they offered. How did it change you? - How do you seek out guidance when you need it?

Are you open to mentorship from unexpected sources? Do you cultivate relationships, seek feedback, and remain curious?

Exercise: Writing to Your Mentor

Write a letter to a mentor (real or imagined), expressing gratitude for their influence on your story. What advice would you seek from them now?

- Begin by thanking your mentor for their guidance, support, or inspiration.

- Describe a specific moment when their wisdom made a difference in your life.

- Share where you are on your journey now-your challenges, hopes, and fears.

- Ask for the advice or encouragement you need at this stage.

- Close by reflecting on how you can be a mentor to others.

The Mentor’s Paradox: Strength in Vulnerability

Rodin’s Balzac is both powerful and vulnerable. The massive form, the exaggerated features, the enveloping robe-all suggest strength, but also a kind of exposure. The robe is both armor and shroud, concealing and revealing at the same time.

This paradox is at the heart of mentorship. The mentor is not the invulnerable hero, but the one who has faced their own struggles and is willing to share them. The mentor’s strength lies in their willingness to be seen-not as perfect, but as real.

For leaders, embracing this paradox means being willing to share your own journey, to admit your mistakes, and to model the courage to keep growing. It means recognizing that your greatest influence may come not from your achievements, but from your authenticity.

The Mentor’s Gaze: Looking to the Horizon

One of the most striking features of Rodin’s Balzac is his gaze. The figure leans back, eyes fixed toward the horizon, as if contemplating a distant future or an unseen possibility. This gaze is both introspective and visionary-a reminder that the mentor’s role is not just to guide, but to inspire.

For leaders, the mentor’s gaze is an invitation to look beyond the immediate challenges, to imagine what might be possible, and to encourage others to do the same. The mentor does not dictate the path, but points to the horizon, reminding the hero that the journey is ongoing, and that the greatest adventures are yet to come.

The Mentor’s Gift: Empowerment and Transformation

Ultimately, the mentor’s greatest gift is empowerment. The mentor does not walk the path for the hero, but helps them find the courage, wisdom, and resilience to walk it themselves. The mentor’s presence is a catalyst for transformation-a reminder that the hero is capable of more than they imagined.

Rodin’s Balzac, with its monumental presence and enigmatic power, stands as a symbol of this gift. It challenges us to see ourselves not as finished products, but as works in progress-always becoming, always growing, always reaching for something greater.

For leaders, the mentor’s gift is the ability to see-and to help others see-the potential within. It is the willingness to invest in others, to share wisdom, to offer encouragement, and to model the courage to keep moving forward.

Conclusion: Becoming the Mentor

As you stand before Rodin’s Monument to Balzac, take a moment to reflect on the mentors who have shaped your journey. Honor their wisdom, their courage, and their willingness to share their struggles as well as their successes.

But do not stop there. The true legacy of the mentor is not just in the guidance they offer, but in the inspiration they provide for others to become mentors themselves. As you continue on your journey, ask yourself: How can I be a mentor to others? How can I share my story, my struggles, and my wisdom in a way that empowers those around me?

The mentor’s path is not easy. It requires vulnerability, courage, and a willingness to embrace imperfection. But it is also the path of greatest impact-the path that transforms not only the hero, but the world.

Rodin’s Balzac, rough and unfinished, stands as a testament to the power of authenticity, the importance of perseverance, and the enduring mystery of mentorship. Let it remind you that you are not alone on your journey, and that the greatest adventures are those we undertake together.

5. Crossing the Threshold – “The Walking Man”

Introduction: The Leap into the Unknown

In every great story, there comes a moment when the hero must act. After the call to adventure, after wrestling with fear and doubt, after seeking the guidance of mentors, comes the moment of commitment. This is the stage called Crossing the Threshold-the point of no return, when the protagonist leaves the familiar world behind and steps into the unknown.

For leaders, this is the leap into a new project, role, or mindset. It is the decision to act, to risk, to grow. It is the moment you stop preparing and start doing, even if you do not feel fully ready. The journey ahead is uncertain, but the commitment is real.

Auguste Rodin’s The Walking Man (1907) is the embodiment of this moment. A dynamic, unfinished figure striding forward, missing arms and a head, yet full of energy and purpose, The Walking Man captures the essence of the “warrior” archetype: action, courage, and momentum. The sculpture’s radical incompleteness is not a flaw, but a statement-a declaration that the journey is not about having all the answers, but about moving forward despite uncertainty.

The Sculpture: Fragmentation and Power

The Walking Man is one of Rodin’s most celebrated and radical works. It began its life as a series of studies for an earlier sculpture, Saint John the Baptist Preaching (1878), which itself was a breakthrough in Rodin’s career. Rodin made separate plaster studies of the figure’s components-legs, torso, arms, head-and much later, he returned to these fragments, grafting the torso from one project onto the legs of another.

The result is a figure that is both incomplete and utterly alive. The arms and head are missing, yet the body surges forward in a powerful stride. The hips and torso twist with energy, the legs are planted in a wide, triangular stance, the back foot turned to the side while the front foot points straight ahead. The surface is rough, jagged, and textured, alive with the marks of Rodin’s hand. Light and shadow play across the uneven skin, creating a sense of constant motion.

Critics at the time were baffled, even scandalized. How could a statue without a head or arms be considered finished? How could it depict a man, let alone a man walking? But Rodin was uninterested in conventional completeness. He was after something deeper: the essence of movement, the raw power of commitment, the moment when the body-and the spirit-surge into action.

The Warrior Archetype: Action and Courage

In the Hero’s Journey, crossing the threshold is the moment when the hero becomes a warrior. The time for contemplation is over; the time for action has begun. The warrior does not wait for certainty or perfection. The warrior acts, trusting that clarity will come through movement.

The Walking Man is the perfect embodiment of this archetype. The figure’s stride is purposeful, even if the destination is unclear. The missing head and arms suggest that the journey is not about having all the answers or being fully prepared. It is about moving forward, despite uncertainty.

For leaders, this is the leap into a new role, the launch of a bold initiative, the decision to speak up or step out. It is the moment you say yes to the adventure, even if you do not know where it will lead. The warrior archetype is not about aggression, but about commitment, discipline, and the willingness to face risk for the sake of growth.

The Radical Notion of Incompleteness

Rodin’s Walking Man introduced radical notions of sculptural truncation and assembly into the modern artistic canon. By combining a torso and a pair of legs from different projects, Rodin created a work that is neither organically functional nor physically whole. Yet, he considered it finished because it captured the essence of movement.

This radical incompleteness is a metaphor for every journey of transformation. When you cross the threshold, you are not a finished product. You are a work in progress, incomplete, uncertain, but moving forward. The journey itself will shape you, refine you, and reveal your true form.

Rodin was deeply influenced by the art of Classical antiquity, where many surviving sculptures are headless, armless, or otherwise fragmented. He amassed a collection of over 6,000 antiquities, including many fragments of marble sculpture, which he regarded as complete objects in themselves. In his own work, he introduced the idea of the headless, limbless torso as an object of art in its own right, much influencing his contemporaries and the generations that followed.

The Genesis of The Walking Man

The genesis of The Walking Man is a story of artistic evolution and risk-taking. Rodin started with his life-sized sculpture Saint John the Baptist Preaching, which was considered by many to be his first life-sized masterpiece. The figure of Saint John is the embodiment of determination, with his head held high and his feet securely planted into the earthen bronze; his body balanced with the right arm extended as a counterweight to the contrapposto turn of his hips. Rodin was clearly interested in representing movement in this statue and continued to explore ways to perfect his “walking man”.

Years later, Rodin rediscovered the clay torso, by then cracked and fissured like an ancient statue, in his studio. He cast it in bronze as an autonomous sculpture, powerfully expressive in its fragmentary form. Then, he mounted the torso atop the forked legs, the juncture of the two pieces representing the very fulcrum of the body in motion. Stripping away all anecdote and rhetoric, Rodin achieved an expression of pure movement-the powerful forward stride of a seeker, a striver, a prophet, a visionary.

Rodin first exhibited The Walking Man on a tall column at his 1900 retrospective at the Pavillon de l’Alma, and he selected the figure for prominent display at a banquet held in 1903 when he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur. The sculpture made a deep impression on younger artists, notably Henri Matisse, and paved the way for the modernist embrace of fragmentation, abstraction, and the unfinished.

The Power of Movement

One of the most striking features of The Walking Man is its sense of movement. Rodin sculpted a jagged, textured surface instead of the traditionally smooth, unblemished skin that was preferred in the classically-inspired statues of his time. This uneven “skin” enhances the curvature of the calf and abdominal muscles as they tense and twist in preparation for the implied next stride.

The rough surface texture creates a continuous line of movement for the viewer’s eyes to follow. Motion is constant as light and shadow play across the surface. Unlike a sculpture with a smooth surface, light that reflects off of the uneven surfaces highlights its imperfections. Divots become darker and high crests become brighter. As the viewer moves around the statue, the light and dark areas change, appearing to undulate like the swells of the ocean.

Rodin may not have created an overtly twisting and contorting figure, but the impression and implication of movement are very much present. He conveys motion and strength in a figure that is fragmented and seemingly unfinished. Does a statue need to include arms or a head in order for it to be declared complete? Do all limbs need to be present to depict movement? Rodin’s answer is no.

The Leap in Leadership: Embracing Uncertainty

For leaders, The Walking Man is a powerful metaphor for the moment of commitment. Crossing the threshold is rarely a tidy or complete process. You may feel unprepared, incomplete, or unsure of your direction. But the act of stepping forward is itself transformative.

The missing head and arms remind us that you do not need to have everything figured out before you begin. The journey will require you to improvise, adapt, and learn as you go. What matters is the willingness to act, to risk, to move. The stride of The Walking Man is a declaration: “I am going forward, even if I do not know exactly where I am going.”

This is the essence of leadership. The world is full of uncertainty, complexity, and change. Waiting for perfect clarity or complete readiness is a recipe for stagnation. The leader’s task is to move forward, to create momentum, to inspire others by example.

The Influence of Antiquity and Modernity

Rodin drew energy and inspiration from the art of Classical antiquity, absorbing and assimilating the models of ancient Greek and Roman art in his own work in innovative ways. He was particularly fascinated by the fragmentary statues of antiquity, which he saw not as broken, but as complete in their own right. This embrace of incompleteness was revolutionary, anticipating the impact of later artists such as Alberto Giacometti, whose own Walking Man would become an icon of modern art.

Rodin’s willingness to reuse old molds and rework his earlier ideas was also ahead of its time. Like a painter who reworks an old canvas, Rodin would continue to alter an existing form until it developed a new identity and a new narrative1. The Walking Man is the product of this process-a work that is both ancient and modern, rooted in tradition yet radically innovative.

The Walking Man as a Universal Symbol

The Walking Man is both a humble image of an ordinary man and a potent symbol of humanity7. The act of walking is universal-a symbol of progress, journey, and the passage of time. In Rodin’s hands, the walking man becomes a seeker, a striver, a visionary. The figure’s stride is not just a physical act, but a metaphor for the courage to move forward, to cross thresholds, to embrace the unknown.

For leaders, this universality is both a comfort and a challenge. It reminds us that we are not alone in our struggles, that the journey into the unknown is a shared human experience. But it also challenges us to move beyond hesitation, to recognize that within our uncertainty lies the possibility of growth and transformation.

The Decision to Act: Threshold Moments in Leadership

Every leader faces threshold moments-times when a decision must be made, a risk taken, a new path chosen. These moments are rarely easy. They are often accompanied by fear, doubt, and resistance. But they are also the moments that define us, that shape our character, that set us on the path to greatness.

The Walking Man stands as a reminder that action is the antidote to paralysis. The figure’s stride is purposeful, decisive, and full of energy. The missing head and arms are not a handicap, but a liberation-a release from the need for certainty, a permission to act without knowing all the answers.

For leaders, the lesson is clear: Do not wait for perfect conditions. Do not wait until you feel complete or fully prepared. The journey will shape you, refine you, and reveal your true form. The act of moving forward is itself an act of creation.

Reflection: Questions for Leaders

- What first step can you take toward your new story?

Identify a concrete action you can take to move forward, even if it feels small or uncertain. - Where do you need to show courage in your leadership?

Reflect on the areas where you are hesitating, holding back, or waiting for more information. What would it look like to act anyway? - What is holding you back from moving forward?

Name the fears, doubts, or obstacles that are keeping you from crossing the threshold. Are they real, or are they stories you are telling yourself?

Exercise: The Symbolic Step Forward

Take a symbolic step forward in the gallery. As you do, reflect on a recent decision where you crossed a threshold in your leadership. What did you learn?

- Stand before The Walking Man and take a single step forward. Feel the weight shift in your body, the sense of movement and commitment.

- Recall a recent moment when you made a decision to act, even if you did not feel fully prepared. What was the outcome? What did you learn about yourself?

- Write down your reflections. How can you apply this lesson to your current challenges?

The Walking Man and the Modern Imagination

The Walking Man has had a profound influence on the modern imagination. Its radical incompleteness, its embrace of movement and process, its rejection of traditional notions of finish and perfection-all have inspired generations of artists, writers, and thinkers.

Rodin’s willingness to leave the figure unfinished was a declaration of artistic freedom. It was a rejection of the idea that art-or life-must be polished, complete, or perfect to be valuable. Instead, Rodin celebrated the beauty of becoming, the power of the journey, the courage to move forward despite uncertainty.

For leaders, this is a powerful message. The world is changing rapidly, and the old certainties are disappearing. The ability to act, to adapt, to move forward without all the answers is more important than ever. The leader who waits for perfection will be left behind. The leader who embraces the journey, who is willing to cross the threshold, will shape the future.

The Walking Man in Context: Legacy and Influence

Rodin’s Walking Man paved the way for the modernist embrace of fragmentation, abstraction, and the unfinished. It inspired artists such as Henri Matisse, Umberto Boccioni, and Alberto Giacometti, whose own Walking Man would become one of the most iconic images of modern art.

The sculpture’s influence extends beyond the art world. It has become a symbol of human resilience, progress, and the courage to move forward in the face of adversity. In times of crisis, uncertainty, or change, The Walking Man stands as a beacon-a reminder that the journey is more important than the destination, that action is more powerful than hesitation, that the willingness to step forward is the first step toward greatness.

Conclusion: The Journey Begins with a Step

As you stand before Rodin’s Walking Man, take a moment to honor your own journey. Recognize the courage it takes to move forward, to cross thresholds, to embrace the unknown. The missing head and arms are not a flaw, but a reminder that you do not need to have everything figured out before you begin. The journey will shape you, refine you, and reveal your true form.

The act of stepping forward is itself an act of creation. It is a declaration of commitment, a leap of faith, a promise to yourself and to those you lead. The world is waiting for your stride, your courage, your willingness to act.

The journey begins with a single step. Take it.

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies – “The Burghers of Calais”

Introduction: The Crucible of Challenge

No journey worth taking is without trials. After the hero has answered the call, faced their doubts, and received the guidance of a mentor, they step into the world of adventure-a world filled with tests, allies, and enemies. In the Hero’s Journey, this is the crucible where character is forged, relationships are tested, and the hero’s resolve is pushed to its limits.

For leaders, this stage is the lived reality of every major project, transformation, or crisis. It is the stretch of the journey where vision meets resistance, where the need for support becomes clear, and where the true nature of obstacles-both external and internal-comes into focus. It is here that the leader must learn to rely on others, to navigate conflict, and to grow through adversity.

No work of art captures the complexity and humanity of this stage more powerfully than Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais (1884–89). This monumental bronze group, depicting six citizens sacrificing themselves to save their city during the Hundred Years’ War, is a masterclass in the portrayal of ordinary people facing extraordinary circumstances. Their faces show anguish, resolve, and solidarity-a testament to the power of community, teamwork, and courage in the face of fear.

The Historical Moment: Sacrifice and Solidarity

To understand the depth of Rodin’s achievement, it is essential to revisit the historical episode that inspired The Burghers of Calais. In 1347, after an eleven-month siege by the English army under King Edward III, the French port city of Calais was on the brink of starvation. With no hope of relief, the city’s leaders were forced to negotiate surrender.

According to the chronicler Jean Froissart, Edward offered to spare the people of Calais if six of its leading citizens would surrender themselves to him, presumably to be executed. The first to volunteer was Eustache de Saint Pierre, one of the wealthiest and most respected burghers. Five others joined him. Wearing sackcloth and halters around their necks-a sign of submission-and carrying the keys to the city, they walked out to face their fate. Unknown to them, their lives would ultimately be spared by the intervention of Queen Philippa of Hainault, who pleaded for mercy.