Introduction: Paris as Your Living Story

Paris is a city of stories-its cobblestones echo with the footsteps of visionaries, artists, and seekers who came here to reinvent themselves. In the 1920s, a young Ernest Hemingway arrived with little money and big dreams. He found inspiration in Paris’s cafés, gardens, and bookshops, and in the company of fellow expatriates-the so-called Lost Generation. His memoir, A Moveable Feast, is more than a recollection; it’s an invitation to see your life as a legend in the making.

This journey is not just a literary pilgrimage. It’s a leadership adventure, a creative quest, and a mirror for your own transformation. Guided by Peter de Kuster’s Hero’s Journey model-twelve stages, twelve archetypes-you’ll walk in Hemingway’s footsteps through twelve iconic Paris locations, each a portal to a new chapter in your own legend. At every stop, you’ll encounter questions and exercises designed to help you reflect, dream, and lead with greater authenticity. Because you are the storyteller of your life, and only you can create your own legend-or not.

Why Walk Paris in Hemingway’s Footsteps?

Hemingway’s Paris was a city of paradox: poverty and joy, discipline and wildness, solitude and community. It was a city where every day held the promise of discovery. “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man,” Hemingway wrote, “then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.” This is not nostalgia-it is a call to action. Paris becomes a moveable feast when you dare to live as a creator, to turn ordinary moments into extraordinary memories, and to lead yourself and others with curiosity and courage.

The Benefits for Travellers

- Personal Leadership: This journey awakens your sense of agency. At each stage, you’ll explore your values, strengths, and vision for the future.

- Creative Inspiration: Walking the same streets as Hemingway, you’ll tap into the city’s creative energy and your own capacity for reinvention.

- Deeper Connection: Through reflection and storytelling, you’ll connect more deeply with yourself, your travel companions, and the spirit of Paris.

- Legacy and Meaning: By the end of your journey, you’ll have crafted a new chapter in your own legend-one you can carry with you, wherever you go.

How to Use This Journey

At each of the twelve locations, you will encounter:

- A stage of the Hero’s Journey and its archetype

- A brief story or insight from Hemingway’s Paris

- Reflective questions to explore your own leadership story

- A creative exercise to help you embody the lesson

Whether you walk alone or with others, take time to pause, reflect, and let the city-and your imagination-guide you. Bring a journal, an open mind, and a willingness to be surprised.

The 12-Stage Leadership Walking Journey in Paris

1. Ordinary World / The Innocent

Location: 74 Rue Cardinal Lemoine (Hemingway’s First Paris Apartment)

Paris, 1922: The Beginning of a Legend

On a damp January morning in 1922, Ernest Hemingway and his wife Hadley Richardson arrived at 74 Rue Cardinal Lemoine, tucked in the heart of the Latin Quarter, Paris. The city was gray and wet, but for the Hemingways, it shimmered with possibility. Their new home was a modest two-room flat on the third floor, with no hot water and no toilet except for a shared “antiseptic container” in the hallway-a far cry from comfort, but a world away from the constraints of their old lives.

The apartment was small and oddly shaped, with slanting floors and just enough room for a mattress on the floor, a few pictures on the wall, and a piano for Hadley. The rent was 250 francs a month, about $18, and included the services of a femme de ménage, Marie Cocotte, who would cook for them each night. Outside their window, Hemingway could see the wood and coal man’s place, the golden horse’s head above the Boucherie Chevaline, and the green-painted co-op where they bought cheap, good wine. Below was the Bal du Printemps, a dance hall whose music floated up on summer nights.

Despite the privations, Hemingway later wrote, “With a fine view and a good mattress and springs for a comfortable bed on the floor, and pictures we liked on the walls, it was a cheerful, gay, flat. We were very poor and very happy”. This was the ordinary world of the young Hemingway-a world of hope, innocence, and uncertainty, where every day was an adventure and every hardship a story in the making.

The Innocent’s World: Hope and Hunger

Hemingway’s Paris was not the glamorous city of postcards. Their apartment had no hot water, and the “toilet” was little more than a hole in the floor shared by the building’s residents. The couple often went hungry, stretching their meager budget over simple meals-radishes, foie de veau with mashed potatoes, endive salad, and apple tart8. Yet, in these lean days, they found joy in small pleasures: a walk through the Latin Quarter, a glass of cheap wine, the company of each other and their friends.

The Latin Quarter itself was a world of contrasts. Just steps away was the Place de la Contrescarpe, with its bustling cafés and colorful characters. Hemingway would sit at the Café des Amateurs, watching the “drunkards and the sportifs,” though he often avoided it for its smell and raucousness. This was far from the fashionable cafés of Montparnasse, but it was alive with the energy of real life-messy, unpredictable, and inspiring.

In these early Paris days, Hemingway was a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star. He spent his mornings writing in a rented attic room at 39 Rue Descartes, seeking the solitude he needed to hone his craft. In the afternoons, he would walk the city, notebook in hand, soaking in the sights, sounds, and stories that would later fill his books.

The Innocent’s Encounters: Friendship and Influence

Paris in the 1920s was a magnet for artists and writers. At Rue Cardinal Lemoine, Hemingway was just a short walk from James Joyce, who finished Ulysses at No. 71. Through the city’s cafés and salons, he forged friendships with literary giants like Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, and painters like Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso. These relationships were instrumental in Hemingway’s development as a writer, offering him both mentorship and challenge.

But at this stage, Hemingway was still an innocent-full of hope, eager to learn, and not yet hardened by fame or disappointment. He was hungry, not just for food, but for experience, for stories, and for a place in the world of letters. The city, with its ancient stones and endless possibilities, was both a playground and a crucible.

The Ordinary World as a Mirror

The story of Hemingway’s arrival in Paris is not just his story-it is the universal story of beginning, of stepping into a new world with hope and uncertainty. It is the story of every leader, artist, or dreamer who has ever dared to leave the familiar behind in search of something more.

Reflect:

- What is your “ordinary world” right now?

- Where do you feel innocent, hopeful, or naïve?

- What are the comforts and constraints of your current life?

- What small joys sustain you? What hungers drive you?

Exercise: Letter to Your Younger Self

Take a moment to write a letter to your younger self, as if you were standing at the threshold of your own Paris.

- What dreams and beliefs did you hold then?

- What fears and uncertainties did you face?

- What would you tell yourself now, with the wisdom of experience?

- How can you honor the innocence and hope that brought you to where you are?

The Power of the Innocent

Hemingway’s time at 74 Rue Cardinal Lemoine was a time of innocence, but not ignorance. It was a time of openness to the world, of willingness to be shaped by experience, and of courage to begin, even when the outcome was uncertain. The ordinary world is not a place to escape, but a place to honor-for it is the soil from which every legend grows.

As you stand at the beginning of your own journey, remember: every legend starts with a single step, a humble room, and a heart full of hope. The city is waiting, and your story is just beginning.

“Such was the Paris of our youth, the days when we were very poor and very happy.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

2. Call to Adventure / The Orphan

Location: Rue Mouffetard (The Bustling Market Street)

Step into the world outside your comfort zone.

Paris, 1922: The Threshold of the Unknown

After settling into their modest apartment on Rue Cardinal Lemoine, Ernest and Hadley Hemingway found themselves perched on the edge of a new life. Just outside their door, the world of Paris beckoned-strange, vibrant, and full of promise and peril. The city was both playground and proving ground, and nowhere was this more vividly felt than on Rue Mouffetard, the ancient artery of the Latin Quarter.

Rue Mouffetard, even in Hemingway’s day, was a “wonderful, narrow, crowded market street”. It ran down the hill from Place de la Contrescarpe to the church of Saint Médard, lined with stalls bursting with produce, fishmongers calling out their wares, butchers and bakers, flower vendors dyeing the gutters purple, and the smells of cheese and roasting chestnuts mingling in the air. It was a living, breathing organism-a microcosm of Paris itself, where every walk was a lesson in the city’s character, and every encounter was a brush with the unknown.

For Hemingway, Rue Mouffetard was more than a market; it was a threshold. Here, he stepped out of the safety of his apartment and into a world that was not his own. He was an American, a foreigner, a young man with little money and big dreams, surrounded by people whose language, customs, and lives were at once fascinating and alien. The street was a daily call to adventure-a challenge to adapt, observe, and find his place in this new world.

The Orphan Archetype: Alone in the Crowd

The archetype of the Orphan is not just about literal abandonment or loss. It is about the moment when you realize you are on your own-when the comforts of the familiar are gone and you must navigate a world that does not know your name. Hemingway, like so many of the Lost Generation, felt this acutely. The war had left its mark on everyone, and the artists, writers, and dreamers who flocked to Paris in the 1920s were, in many ways, orphans-cut off from the certainties of the past, searching for new meaning in a world that had been shattered and rebuilt.

On Rue Mouffetard, Hemingway was both participant and observer. He watched the market women haggle, the children play, the old men drink their wine in the morning sunshine. He was fascinated by the life around him, but he was also aware of his own outsider status. He wrote about the “rowdy Café des Amateurs” on Place de la Contrescarpe, a place he avoided because of its “sour smell of drunkenness,” but also because he did not belong there. He was not yet part of the city’s story; he was learning its language, its rhythms, its secrets.

This sense of being an outsider was both painful and exhilarating. It was the price of adventure-the necessary discomfort that comes with growth. Hemingway’s walks down Rue Mouffetard were acts of courage, small but significant steps into the unknown. Each day, he faced the challenge of making his way in a city that was indifferent to his presence, a city that demanded he prove himself through observation, discipline, and the relentless pursuit of “one true sentence”.

The Lost Generation: A City of Orphans

Hemingway was not alone in his orphanhood. Paris in the 1920s was a gathering place for the Lost Generation-the name Gertrude Stein gave to the young Americans who had been disillusioned by the First World War and sought to reinvent themselves in Europe. Writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, E.E. Cummings, and artists like Picasso and Miró all found their way to Paris, drawn by the promise of freedom, creativity, and the chance to start anew.

But this freedom came at a cost. The Lost Generation were exiles, cut off from their homeland and from the values that had shaped them. They were orphans in a spiritual sense, forced to create their own meaning in a world that no longer made sense. Paris was their laboratory and their refuge, a place where they could experiment with art, love, and identity.

Rue Mouffetard, with its chaos and color, was a daily reminder of this new reality. Hemingway learned to navigate the market, to buy food for Hadley and himself, to stretch their meager budget over meals of radishes, cheese, and cheap wine. He learned to observe without judgment, to find beauty in the ordinary, and to accept the loneliness that came with being a stranger in a strange land.

The Call to Adventure: Stepping Into the Unknown

Every morning, Hemingway would leave his apartment and descend Rue Mouffetard, notebook in hand. The street was a river of life, and he was both swept along and set apart by it. The call to adventure was not a single moment, but a series of small choices-a willingness to be uncomfortable, to be changed, to open himself to the world’s lessons.

He wrote in A Moveable Feast:

“There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached”.

This is the essence of the call to adventure: the realization that life is not static, that you are always being invited to grow, to risk, to become more than you were yesterday.

For Hemingway, the adventure took many forms. It was the discipline of writing every day in his cold garret at 39 Rue Descartes. It was the challenge of making friends with his neighbors, learning their stories, and earning their respect. It was the thrill of discovering new cafés, new books, new ideas. It was the courage to face rejection, poverty, and self-doubt, and to keep going anyway.

The Orphan’s Questions: Where Do You Feel Like an Outsider?

The experience of being an orphan-of stepping into a world that is not your own-is universal. We all have moments when we feel out of place, uncertain, and alone. These moments are not failures; they are invitations to growth. They are the beginning of every great adventure.

Reflect:

- What is calling you to change or grow?

- Where do you feel like an outsider?

- What fears or uncertainties hold you back from answering the call?

- What small acts of courage can you take today to step into the unknown?

Exercise: Your Challenges and Opportunities

List three challenges or opportunities you are facing. What is at stake if you answer-or refuse-the call?

- Challenge/Opportunity #1:

- What is it?

- What would you gain by embracing it?

- What might you lose if you ignore it?

- Challenge/Opportunity #2:

- What is it?

- What would you gain by embracing it?

- What might you lose if you ignore it?

- Challenge/Opportunity #3:

- What is it?

- What would you gain by embracing it?

- What might you lose if you ignore it?

Take time to write your answers. Be honest about your fears and your hopes. Remember, every adventure begins with a single step outside your comfort zone.

The Market Street as Metaphor: Life’s Crowded Possibilities

Rue Mouffetard is more than a street; it is a metaphor for the journey of life. It is crowded, noisy, unpredictable. It is full of temptations and dangers, but also of beauty and possibility. To walk its length is to practice the art of attention-to notice the details, to listen to the stories, to find your place in the flow.

Hemingway learned to see the world through the lens of the orphan-curious, open, willing to be changed. He learned that the adventure is not always glamorous; sometimes it is a matter of buying potatoes, of listening to a neighbor’s gossip, of writing one true sentence in a cold room. But in these small acts, the legend is born.

The Orphan’s Gift: Empathy and Resilience

The experience of being an outsider can be painful, but it is also a source of strength. It teaches empathy-the ability to see the world through another’s eyes. It teaches resilience-the capacity to keep going when the way is hard. Hemingway’s years on Rue Mouffetard shaped him not just as a writer, but as a human being, capable of compassion, discipline, and courage.

As you walk your own Rue Mouffetard-literal or metaphorical-remember that every step you take into the unknown is a step toward your own legend. The world may not know your name, but you have the power to write your story, to find your place, to answer the call.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Paris

Imagine yourself now, standing at the top of Rue Mouffetard. The market is alive with color and sound. You are a stranger here, but you are also a participant in the great adventure of life. You have choices to make, risks to take, stories to discover. The city is waiting, and so is your own legend.

Take a deep breath. Step into the crowd. Let yourself be changed.

“Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you brought to it. But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.”

3. Refusal of the Call / The Caregiver

Location: 39 Rue Descartes (Hemingway’s Writing Studio)

Face the doubts and responsibilities that hold you back.

The Attic Room: Between Duty and Dream

After the first flush of Parisian adventure, after the thrill and anxiety of being a stranger on Rue Mouffetard, Hemingway’s days settled into a rhythm of discipline and doubt. The third stage of the hero’s journey is rarely glamorous. It is the quiet, often invisible, struggle between the call of your own dreams and the responsibilities that tie you to others. For Hemingway, this struggle played out in a cold, cramped attic room at 39 Rue Descartes.

In 1922, finding his apartment with Hadley too cramped and noisy for serious work, Hemingway rented a small garret at the top of a former hotel, where the poet Paul Verlaine had died twenty-five years before. The room was simple: a fireplace, a table, a chair, and a window that looked out over the rooftops of Paris. It was a place of solitude and focus, but also of hunger and uncertainty. “I was always hungry with the walking and the cold and the working,” Hemingway wrote. “The fireplace drew well in the room and it was warm and pleasant to work. […] Up in the room I had a bottle of kirsch […] and I took a drink of kirsch when I would get toward the end of a story or toward the end of the day’s work.”

Here, Hemingway practiced the discipline that would become his hallmark. He wrote stories about his childhood in Michigan, about fishing and hunting, about the people and places he had known. He set himself the task of writing “one story about each thing I knew about.” When he got stuck, he would look out over the chimneys and think, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

But writing did not come easily. It was, as he later described, a “perpetual challenge,” a craft learned only through long and laborious practice. Each day, Hemingway faced the blank page with a mixture of hope and dread. Each day, he battled the temptation to give up, to take the easy way, to let the responsibilities of marriage, family, and survival crowd out the fragile voice of his own ambition.

The Weight of Responsibility

Hemingway’s Paris was not the carefree Bohemia of legend. He and Hadley were poor, often hungry, and always aware of how precarious their situation was. The money he earned from journalism was barely enough to cover rent and food. When he gave up his steady reporting job to focus on fiction, the family’s finances became even more strained. “Hunger was good discipline,” he wrote in A Moveable Feast, but it was also a source of anxiety and guilt.

Hadley, too, carried her own burdens. She was far from home, learning to navigate a foreign city, supporting her husband’s dreams even as she sacrificed her own comforts. When their son John (“Bumby”) was born, the responsibilities multiplied. Hemingway would rise early to write, sometimes in the company of his sleeping child and the family cat. The demands of fatherhood, marriage, and art pulled him in different directions.

In the attic at 39 Rue Descartes, Hemingway was not just a writer. He was a husband, a father, a provider. Every hour spent at the desk was an hour not spent earning money, caring for his family, or tending to the small crises of daily life. The tension between duty and desire, between self and others, was constant and real.

The Caregiver Archetype: The Pull of Others’ Needs

The third stage of the hero’s journey is often marked by hesitation-a refusal of the call to adventure. For Hemingway, this refusal was not dramatic but subtle, woven into the fabric of his daily life. It was the voice that said, “Who are you to think you can be a great writer?” It was the fear that pursuing his own dreams would mean failing those who depended on him.

The Caregiver archetype is powerful. It is the part of us that wants to nurture, protect, and provide. It is the voice of responsibility, of loyalty, of love. But it can also become a trap-a reason to put off our own growth, to sacrifice our own calling for the sake of others. In Hemingway’s Paris, the struggle between Caregiver and Creator was never resolved; it was a tension he carried all his life.

Doubt and Discipline

Writing, for Hemingway, was a “fiercely competitive literary prize fight,” a battle against both his contemporaries and his own limitations1. Each day in the attic was a test of willpower. He disciplined himself to write until he had “said what I had to say,” and then he would stop, trusting his subconscious to work on the story until the next day. He learned not to talk about his writing, not to dissipate its energy in conversation, but to save it for the page.

But discipline was not always enough. There were days when the words would not come, when the cold seeped into his bones, when the hunger gnawed at his resolve. There were days when the responsibilities of marriage and fatherhood felt overwhelming, when the dream of becoming a great writer seemed impossibly far away.

Hemingway’s refusal of the call was not a single moment of weakness, but a daily struggle. It was the temptation to settle for less, to accept the comfort of the familiar, to let the needs of others eclipse his own. It was the fear of failure, the fear of selfishness, the fear of disappointment.

The Caregiver’s Dilemma: Love and Sacrifice

Hemingway loved Hadley deeply. Their early years in Paris were marked by tenderness and laughter, by shared hardships and small joys. But love, for Hemingway, was always complicated. He felt the weight of Hadley’s sacrifices, the loneliness she endured, the dreams she set aside for his sake. He worried that his ambition would hurt her, that his hunger for greatness would leave her behind.

As their family grew, so did the demands on Hemingway’s time and energy. The arrival of Bumby brought both joy and anxiety. Hemingway wanted to be a good father, to provide for his son, to give him the security and love he had not always known himself. But the call of the page was relentless, and the fear of failure was ever-present.

In the attic at 39 Rue Descartes, Hemingway faced the central dilemma of the Caregiver: How do you balance your own dreams with the needs of those you love? How do you honor your responsibilities without losing yourself in them? How do you find the courage to say yes to your own calling, even when it means saying no to others?

The Attic as Sanctuary and Prison

The garret at 39 Rue Descartes was both a sanctuary and a prison. It was a place where Hemingway could escape the noise and chaos of daily life, where he could focus on the work that mattered most to him. But it was also a place of isolation, of hunger, of doubt. The window looked out over the rooftops of Paris, a reminder of the world beyond, of the life he was sacrificing for the sake of his art.

Hemingway wrote about the discipline of writing, the need to “pare down” his sentences to the bare essentials, to capture the truth of experience in the simplest possible language. But the discipline of writing was mirrored by the discipline of living-by the choices he made every day to put his work first, to endure hunger and cold, to risk failure for the sake of something greater.

The Refusal of the Call: A Universal Struggle

Hemingway’s struggle at 39 Rue Descartes is not just his own. It is the universal struggle of anyone who has ever dared to dream, to create, to lead. It is the moment when the call to adventure is met with doubt, with fear, with the pull of duty and love. It is the moment when you must choose between the safety of the known and the risk of the unknown, between the comfort of others’ expectations and the challenge of your own ambition.

Reflect:

- What responsibilities or fears make you hesitate?

- Who do you feel responsible for?

- How do you balance your own dreams with the needs of those you love?

- What would it mean to say yes to your own calling?

Exercise: When You Put Others’ Needs Before Your Own

Write about a time you put others’ needs before your own dreams. What did you learn?

- What was the situation?

- What did you sacrifice?

- How did it feel to put someone else first?

- What did you gain from the experience?

- Looking back, would you make the same choice again? Why or why not?

Take time to reflect deeply. Be honest about the costs and the rewards. Remember, the refusal of the call is not a failure, but a necessary stage in the journey. It is the moment when you test your resolve, when you clarify your values, when you prepare yourself for the challenges ahead.

The Turning Point: From Refusal to Commitment

For Hemingway, the attic at 39 Rue Descartes was a crucible. It was where he learned the discipline of writing, the courage to face his fears, and the resilience to keep going in the face of doubt. It was where he discovered that the only way forward was through-the only way to honor his responsibilities was to honor his own calling first.

In time, Hemingway would leave the attic behind. He would go on to write The Sun Also Rises, to travel the world, to become the legend he had dreamed of becoming. But the lessons of 39 Rue Descartes stayed with him-the discipline, the humility, the courage to begin again each day.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Attic Room

Imagine yourself now, standing at the top of a narrow staircase, the city spread out beneath you. You are alone with your thoughts, your doubts, your dreams. The world outside is full of noise and demands, but here, in this quiet room, you face the blank page of your own life.

What will you write? What will you risk? What will you sacrifice? The choice is yours.

“All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

4. Meeting the Mentor / The Mentor

Location: Shakespeare & Company (12 Rue de l’Odéon)

Find wisdom and encouragement for your journey.

The Bookshop at the Heart of Paris

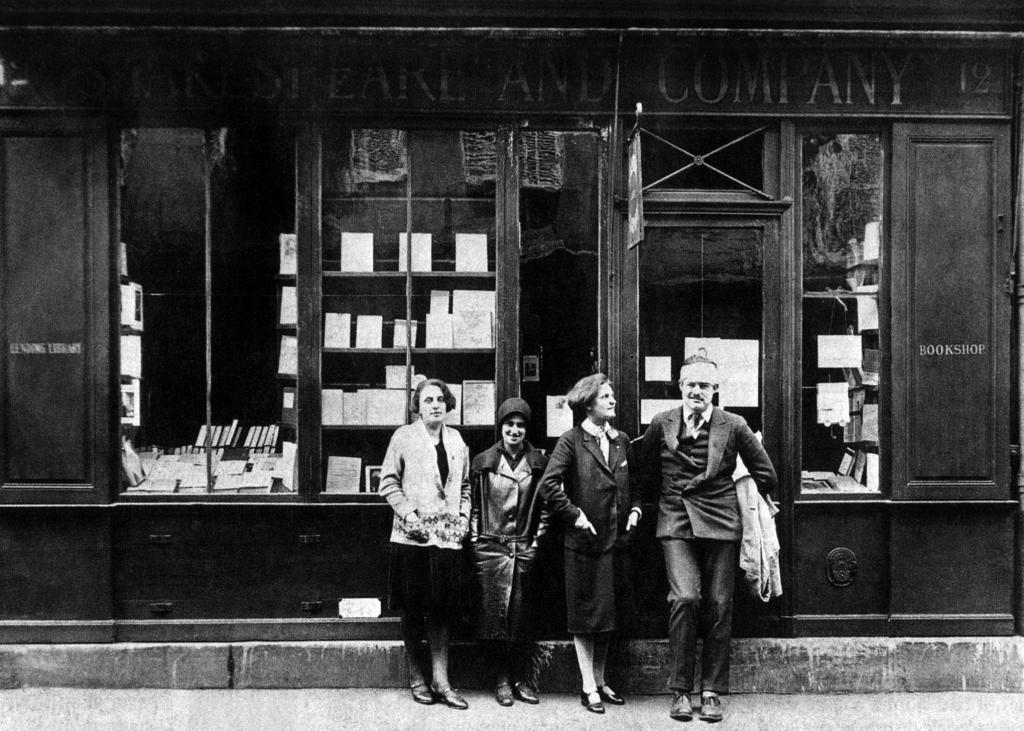

In the heart of the Left Bank, on a narrow street lined with bookshops, cafés, and the echoes of centuries of literary ambition, stands a modest storefront that changed the course of modern literature: Shakespeare & Company. In the early 1920s, this was not yet the tourist mecca it would become, but a living, breathing sanctuary for the lost, the hopeful, and the brilliant. For Ernest Hemingway, newly arrived in Paris, the bookshop at 12 Rue de l’Odéon was a beacon in the fog-a place where he would meet his mentor, Sylvia Beach, and find the wisdom and encouragement to shape his destiny.

Sylvia Beach: The Mentor’s Spirit

Sylvia Beach was not a writer herself, but her influence on the writers of her era was profound. Born in Baltimore in 1887, she grew up in a household shadowed by her parents’ unhappy marriage, but also rich in books and ideas. Her father’s work as a Presbyterian minister took the family to Paris, and for Sylvia, this was the beginning of a lifelong love affair with the city. She studied French literature at the Sorbonne, worked with the Red Cross in Europe, and became fluent in French, Spanish, and Italian.

Inspired by her partner Adrienne Monnier, who ran the French-language bookshop La Maison des Amis des Livres, Sylvia opened Shakespeare & Company in 1919. It was the only English-language bookshop in Paris at the time, and quickly became a magnet for expatriates, artists, and dreamers. The shop was more than a store-it was a lending library, a post office, a bank, a salon, and, for many, a home.

Hemingway’s First Encounter

Hemingway’s first encounter with Sylvia Beach was marked by shyness and curiosity. He and Hadley had arrived in Paris in December 1921, and within a week, Hemingway found himself drawn to the little shop with the green façade and the welcoming windows. The shop was warm, cheerful, and filled with the scent of books and possibility. “Sylvia had a lively, sharply sculptured face, brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal’s and as gay as a young girl’s,” Hemingway wrote in A Moveable Feast. “She was kind, cheerful and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip. No one that I ever knew was nicer to me”.

Sylvia Beach was more than a bookseller. She was a patron, a confidante, and a champion of talent. She lent Hemingway books from her library-sometimes far more than his subscription allowed-urged him to eat when he was skipping meals, and encouraged him to pursue his fiction even when money was tight and self-doubt crept in. For Hemingway, who was still finding his voice and his place in the world, this generosity was transformative.

Shakespeare & Company: A Sanctuary for the Lost Generation

The bookshop was more than a store; it was a crossroads for the Lost Generation. Here, Hemingway met James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and countless other writers and artists who were redefining literature and art. Sylvia Beach’s shop was a lending library, a publishing house (she famously published Joyce’s Ulysses when no one else would), and a salon where ideas were exchanged, friendships were forged, and legends were born.

Beach’s belief in Hemingway’s talent was unwavering. Her encouragement helped him weather the storms of rejection and poverty, and her shop gave him a place to read, to think, and to dream. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway writes of Beach’s generosity: “She made you feel that you were a very good writer and that you could write even better than you thought you could”.

The Mentor’s Wisdom

Sylvia Beach’s mentorship was subtle but powerful. She did not lecture or impose; she listened, encouraged, and believed. She gave Hemingway access to her library, introduced him to other writers, and offered practical help when times were tough. She modeled resilience, creativity, and kindness. Even when facing adversity-such as the Nazi occupation, which forced her to close her beloved shop-Sylvia Beach remained true to her values, supporting her friends and documenting her experiences for future generations.

French author André Chamson once said Beach “did more to link England, the United States, Ireland, and France than four great ambassadors combined”3. She was a cultural visionary, a connector, and a protector of the right to write.

The Mentor Archetype: Finding Your Own Guide

The Mentor is a crucial figure in every hero’s journey. Whether it is a wise teacher, a supportive friend, or a chance encounter with a stranger, the Mentor offers guidance, encouragement, and perspective. The Mentor sees your potential when you cannot, and helps you find the courage to continue when the path is uncertain.

For Hemingway, Sylvia Beach embodied the Mentor archetype. She was a source of wisdom, a model of integrity, and a reminder that greatness is not achieved alone. Her faith in him was a lifeline-a reminder that his voice mattered, even when he doubted himself.

The Ripple Effect of Mentorship

Sylvia Beach’s legacy is not just the success of the writers she nurtured, but the ripple effect of her generosity. She published Ulysses when no one else would, risking her own livelihood for the sake of art. She gave Hemingway, Joyce, Fitzgerald, and others a place to grow and connect. Her life’s work continues to inspire, as Shakespeare & Company remains a beacon for writers and readers from around the world.

Reflect

- Who has mentored or inspired you?

- What wisdom do you need right now?

- Where do you find encouragement when you feel lost or uncertain?

- How do you honor the mentors in your life?

Exercise: Thank Your Mentor

Write a thank-you note (real or imagined) to a mentor. What did they teach you about leadership or creativity?

- Who were they, and how did you meet?

- What did they see in you that you could not see in yourself?

- What lessons or encouragement did they offer?

- How did their belief in you change your path?

- What would you say to them now, if you could?

If you cannot think of a single person, reflect on the small acts of kindness, wisdom, or inspiration you have received from unexpected sources-a teacher, a colleague, a friend, a stranger, or even a book.

The Legacy of Shakespeare & Company

The story of Hemingway and Sylvia Beach is not just a tale of literary Paris; it is a lesson in the power of community and mentorship. Shakespeare & Company continues to inspire writers and dreamers from around the world-a living testament to the belief that art, kindness, and courage can change lives.

As you walk your own path, remember that you are not alone. There are mentors waiting to be found-in people, in books, in the world around you. Seek them out, honor their gifts, and, when the time comes, become a mentor yourself.

“No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

5. Crossing the Threshold / The Explorer

Location: Place de la Contrescarpe

Step boldly into the unknown.

The Crossroads of Paris: Place de la Contrescarpe

In the early 1920s, Paris was a city in recovery and reinvention. The scars of the Great War were still fresh, but the city pulsed with the energy of artists, writers, and dreamers who had come to rebuild their lives and their art. For Ernest Hemingway, Place de la Contrescarpe was the literal and symbolic crossroads where he left the safety of his modest apartment at 74 Rue Cardinal Lemoine and stepped into the exhilarating chaos and possibility of Paris.

Place de la Contrescarpe, a lively square in the heart of the Latin Quarter, was-and remains-a hub of activity. In Hemingway’s day, it was the epicenter of nightlife in the neighborhood, surrounded by bars, cafés, and the constant flow of students, workers, and bohemians. The square connected several key streets: Rue Mouffetard, with its bustling market; Rue Lacépède; Rue Blainville; and Rue du Cardinal Lemoine, where Hemingway lived with Hadley. The cobblestones of the square carried the footsteps of not only Hemingway but also other literary figures like George Orwell and James Joyce.

To walk into Place de la Contrescarpe was to step into the unknown, to leave behind the familiar routines of home and writing room and immerse oneself in the unpredictable rhythms of the city. It was here that Hemingway became an explorer, not just of Paris, but of his own limits and possibilities.

The Explorer’s Spirit: Leaving the Safe Harbor

Hemingway’s Paris was not the Paris of postcards. It was a city of contrasts: ancient and modern, elegant and rough-edged, welcoming and indifferent. The Latin Quarter, with its narrow streets and crowded markets, was a world unto itself. Place de la Contrescarpe was its beating heart-a place where anything could happen.

Hemingway described the square in A Moveable Feast with both affection and disdain. He wrote of the Café des Amateurs, a haunt of local drunkards, as “the cesspool of the Rue Mouffetard,” a place he avoided because of its “sour smell of drunkenness”. Yet, he was drawn to the life of the square: the music, the laughter, the arguments, the endless flow of humanity. It was a place where he could watch the world go by, where he could observe and learn, where he could test himself against the city’s challenges.

Crossing the threshold into Place de la Contrescarpe was an act of courage. It meant leaving behind the safety of routine and stepping into a world that was unpredictable, sometimes harsh, but always alive. It was here that Hemingway learned to be an explorer-not just of Paris, but of himself.

The Explorer’s Encounters: Discovery and Risk

Every day, Hemingway walked from his apartment on Rue Cardinal Lemoine to Place de la Contrescarpe, then down Rue Mouffetard to the market, or up toward the cafés and bookshops of the Left Bank. Each journey was an exploration, a chance to see something new, to meet someone unexpected, to find inspiration in the ordinary.

The square was a crossroads in every sense. Students from the local lycées crowded the cafés, singing and laughing2. Artists and writers debated in smoky corners. Locals shopped for groceries, gossiped, and argued. Tourists were rare in those days, but the square was never empty. Even in the early morning, as described by modern visitors, the cafés buzzed with quiet energy, the air filled with the aroma of coffee and fresh bread.

For Hemingway, these walks were more than errands; they were rituals of discovery. He watched, listened, and absorbed the life around him. He learned to see the world with a writer’s eye-to notice the details, the gestures, the snatches of conversation that would later find their way into his stories.

But exploration came with risks. The city could be unforgiving. Hemingway was poor, often hungry, and always aware of his outsider status. The square could be rough, especially at night, and the Café des Amateurs was notorious for its rowdy clientele. Yet, Hemingway embraced the risks, knowing that only by stepping into the unknown could he grow as a writer and as a person.

The Explorer Archetype: The Courage to Begin

The Explorer archetype is about curiosity, courage, and the willingness to leave the comfort zone. It is the spirit of adventure that drives us to seek new experiences, to test our limits, to discover who we are and what we are capable of. For Hemingway, Place de la Contrescarpe was the gateway to this journey.

In every hero’s journey, there comes a moment when the protagonist must cross the threshold from the ordinary world into the realm of adventure. For Hemingway, this moment happened every day, with every step into the square, every encounter with the unknown. He was not always fearless, but he was always willing to risk, to learn, to explore.

The Crossroads as Metaphor: Life’s Infinite Possibilities

Place de la Contrescarpe is more than a physical location; it is a metaphor for the crossroads we all face in life. It is the place where paths diverge, where choices must be made, where the future is uncertain but full of possibility. To stand in the square is to stand at the edge of your own story, to ask yourself: What am I willing to risk? What am I hoping to find?

Hemingway’s willingness to explore, to embrace the city’s chaos and possibility, was the foundation of his legend. He understood that greatness is not achieved by staying safe, but by stepping boldly into the unknown.

The Explorer’s Questions: Your Own Threshold

Reflect:

- When have you taken a leap into the unknown?

- What did you risk, and what did you discover?

- What crossroads are you facing now?

- What would it mean to step boldly into the next chapter of your life?

Exercise: Your Crossroads

Describe a time when you crossed a threshold in your life. How did it change you?

- What was the situation?

- What fears or doubts did you face?

- What did you risk by stepping forward?

- What did you discover-about the world, about yourself?

- Looking back, how did this experience shape your journey?

Take time to write your answers. Be honest about the risks and the rewards. Remember, every adventure begins with a single step into the unknown.

The Legacy of Place de la Contrescarpe

Today, Place de la Contrescarpe remains a lively, vibrant square, filled with cafés, terraces, and the hum of conversation. The Café des Amateurs is gone, replaced by Café Delmas, now a cheerful spot popular with students and locals. But the spirit of exploration endures. Visitors still come to sit at the cafés, to watch the world go by, to imagine the young Hemingway walking these streets, hungry for life and story.

The square is a reminder that Paris is, as Hemingway wrote, “a moveable feast”-a city that offers endless opportunities for discovery, for adventure, for reinvention. It is a place where the past and present meet, where every day is a chance to begin again.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Paris

Imagine yourself now, standing in Place de la Contrescarpe. The square is alive with energy, the air filled with the sounds of laughter, music, and conversation. You are at a crossroads, both literal and metaphorical. The city stretches out before you, full of unknown possibilities.

What will you risk? What will you discover? The choice is yours.

Take a deep breath. Step boldly into the unknown. Let yourself be changed.

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies / The Warrior

Location: Closerie des Lilas (Boulevard du Montparnasse)

Face your tests and find your allies.

The Warrior’s Arena: Hemingway at Closerie des Lilas

By the early 1920s, Hemingway had crossed many thresholds in Paris. He had left the safety of his small apartment, braved the bustling markets of Rue Mouffetard, and found wisdom at Shakespeare & Company. But it was at the Closerie des Lilas, a storied café on Boulevard du Montparnasse, that Hemingway truly entered the arena of the warrior-facing daily tests, forging alliances, and measuring himself against rivals in the crucible of literary Paris.

The Café as Battleground and Sanctuary

Opened in 1847, Closerie des Lilas quickly became a gathering place for artists, writers, and thinkers. The café’s history is woven into the fabric of Parisian culture: Zola, Baudelaire, Cézanne, Modigliani, Picasso, Joyce, Stein, Fitzgerald, and so many more made it their haunt. By the 1920s, it was a magnet for the Lost Generation, those expatriate Americans and Europeans seeking meaning and creation after the devastation of World War I.

Hemingway called it “the only decent café in our neighborhood” and made it his home base. He wrote short stories and articles for the Toronto Star here, nursed café crèmes on the terrace, and filled blue-covered French notebooks with drafts of what would become The Sun Also Rises. The Closerie was a place to escape the noise of his apartment, but it was also a place to test himself: to write with discipline, to debate with friends, and to clash with rivals.

The Warrior’s Tests: Discipline and Doubt

Every day at the Closerie was a test of Hemingway’s resolve. Paris was full of distractions: the lure of conversation, the temptations of drink, the easy camaraderie of fellow writers. But Hemingway was fiercely disciplined. He would arrive early, settle at his favorite table, and write until he had done his day’s work-sometimes hours, sometimes only a few sentences. He wrote through hunger, through cold, through the doubts that gnawed at every artist in the city.

But the tests were not only internal. The café was a stage for intellectual combat. Hemingway debated art and politics with Ezra Pound, critiqued manuscripts for Fitzgerald, and sparred with rivals over the direction of modern literature. Every conversation was a duel, every friendship a test of loyalty and ambition.

Hemingway’s warrior spirit was forged in these battles. He learned to defend his ideas, to absorb criticism, and to keep writing in the face of rejection. The Closerie was where he honed his craft and his courage.

Allies and Adversaries: The Circle of the Lost Generation

The Closerie des Lilas was more than a café; it was a crucible for the creative alliances and rivalries that shaped Hemingway’s life and work. Here, he found both allies and adversaries-sometimes in the same person.

Allies:

- Ezra Pound: The poet was a mentor and champion, urging Hemingway to cut unnecessary words and pursue clarity.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald: A friend and rival, Fitzgerald shared drafts of The Great Gatsby with Hemingway at the Closerie, seeking his feedback and approval.

- Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas: Regulars at the café, they offered guidance and a sense of community, even as their relationships with Hemingway grew complicated.

- Sylvia Beach: Though more closely associated with Shakespeare & Company, Beach was part of the Closerie’s literary circle, offering encouragement and support.

Adversaries:

- Rival Writers and Critics: The café was full of strong personalities and clashing egos. Debates were fierce, and not all criticism was friendly.

- The Temptations of Paris: Distraction, self-doubt, and the easy escape of pleasure were constant adversaries.

- Poverty and Uncertainty: Hemingway was always aware of how precarious his situation was. Every franc spent on coffee or food was a gamble.

The Closerie was a place where friendships were forged and tested, where alliances shifted with every conversation, and where every writer measured themselves against the rest.

The Warrior’s Rituals: Writing, Debating, Enduring

Hemingway’s routine at the Closerie was both simple and sacred. He would arrive early, order a café crème, and set out his pencils and notebooks. He wrote with fierce concentration, blocking out the noise around him. When friends arrived-Pound, Fitzgerald, Stein-he would join in their debates, always ready to defend his ideas or challenge theirs.

But the café was also a place of endurance. Hemingway wrote through hunger, through loneliness, through the fear that he would never succeed. He learned to accept criticism, to revise his work, to keep going when others gave up. The Closerie was where he became a warrior-not just in art, but in life.

The Warrior Archetype: Courage, Discipline, and Loyalty

The Warrior archetype is defined by courage, discipline, and the willingness to face tests head-on. For Hemingway, the Closerie des Lilas was the arena where he proved himself-not just to others, but to himself. Every day was a battle: against distraction, against self-doubt, against the easy comforts of mediocrity.

But the Warrior is not only a fighter. The Warrior is loyal to allies, honorable in defeat, and generous in victory. Hemingway’s friendships with Pound and Fitzgerald were marked by both rivalry and deep respect. His willingness to help others, to share advice and encouragement, was as much a part of his legend as his competitive spirit.

The Café as Legend: A Living History

Today, the Closerie des Lilas is a Parisian institution, its history preserved in brass plaques on the tables engraved with the names of its famous regulars. The terrace is lush with lilacs in summer, and the piano bar still echoes with music and conversation. The menu features a “Hemingway beef fillet flambéed with Bourbon,” a tribute to the writer who made the café his home.

But the true legacy of the Closerie is its spirit: a place where artists and dreamers come to test themselves, to find their allies, and to face the challenges of creation.

Reflect

- Who are your allies and adversaries?

- What tests your resolve as a leader?

- How do you respond to criticism and challenge?

- Where do you find the courage to keep going when the way is hard?

Exercise: Mapping Your Circle and Your Tests

- List your allies: Who supports you, challenges you to grow, and believes in your vision?

- List your adversaries: Who or what stands in your way-rivalries, critics, distractions, self-doubt?

- Describe a recent test: What challenged your resolve? How did you respond? What did you learn?

- Write about a time you stood your ground: When did you defend your ideas or values in the face of opposition? How did it feel?

Take time to reflect deeply. The Warrior’s path is not easy, but it is essential. Every test, every ally, every adversary is a part of your legend.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Closerie

Imagine yourself now, sitting at a table at the Closerie des Lilas. The air is thick with history, the voices of artists and writers echoing all around you. You are part of a lineage of warriors-those who dared to create, to debate, to endure.

What tests will you face today? Who will stand with you? What will you write, create, or defend?

Take a deep breath. Pick up your pen. Step into the arena.

“The only decent café in our neighborhood was la Closerie des Lilas, and it was one of the best cafés in Paris.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave / The Seeker

Location: Luxembourg Gardens

Seek clarity and renewal in nature.

Hemingway’s Paris: Seeking Solace in the Luxembourg Gardens

As the seasons shifted in Paris and Hemingway’s life grew more complex, the city’s chaos and creative ferment sometimes threatened to overwhelm him. After the noise and rivalry of the Closerie des Lilas, after the endless debates and the daily tests of will, Hemingway needed a place to clear his mind, to escape temptation, and to reconnect with the deeper currents of his own story. For him, that place was the Jardin du Luxembourg, the Luxembourg Gardens.

A Writer’s Refuge

The Luxembourg Gardens, with their stately chestnut trees, formal flowerbeds, and tranquil fountains, have offered a haven for Parisians since the 17th century. For Hemingway, they were a sanctuary from hunger, from distraction, and from the city’s temptations. He wrote of his walks here in A Moveable Feast, describing how, when money was tight and the bakery windows too tempting, “the best place to go was the Luxembourg gardens where you saw and smelled nothing to eat all the way from the Place de l’Observatoire to the rue de Vaugirard”.

But the gardens were more than a way to avoid spending money; they were a place of renewal. Here, Hemingway could walk among the statues and fountains, watch children sail their boats on the pond, and let the rhythms of nature quiet the noise in his head. In the gardens, he found the space to reflect, to dream, and to seek answers to the questions that haunted him.

The Seeker’s Path

The Seeker archetype is driven by the desire for meaning, for clarity, for something beyond the ordinary. In the Luxembourg Gardens, Hemingway became the Seeker: searching for the right words, for the shape of a story, for the next step in his journey. The gardens offered him a chance to step outside the demands of daily life and listen to the deeper voice within.

Hemingway’s walks were not aimless. Each path through the gardens was a meditation, a way to order his thoughts and prepare for the work ahead. He would sometimes visit the Musée du Luxembourg, drawn especially to the landscapes of Cézanne, which taught him about structure, color, and the discipline of seeing17. He wrote, “If I walked down by different streets to the Jardin du Luxembourg in the afternoon I could walk through the gardens and then go to the Musée du Luxembourg”.

The Gardens as a Living Metaphor

The Luxembourg Gardens themselves are a living metaphor for the journey inward. Created in the early 17th century by Marie de Medici, inspired by the Boboli Gardens of Florence, they have evolved through centuries of revolution, war, and renewal6. The gardens have been a stage for history, a refuge for lovers and dreamers, a place where the ideals of liberty and beauty have survived even the darkest times.

For Hemingway, the gardens symbolized endurance and transformation. They were a reminder that beauty could survive hardship, that peace could be found even in a city of turmoil. The gardens’ statues, paths, and changing seasons mirrored the cycles of his own life: times of hunger and plenty, of loneliness and love, of doubt and inspiration.

The Inmost Cave: Facing the Inner Questions

The “inmost cave” in the hero’s journey is not always a literal place. Often, it is a state of mind-a turning inward, a confrontation with the questions and fears that drive us. For Hemingway, the Luxembourg Gardens were the setting for this inward journey. Here, he faced the uncertainties of his art, the complexities of his marriage, the wounds of his past, and the hopes for his future.

He was not alone in this. Other writers, too, found solace in the gardens. Balzac, in the 1830s, walked here as he wrestled with the characters of Le Père Goriot. The gardens have always attracted seekers: those in search of clarity, of inspiration, of a moment’s peace in a restless world.

Renewal Through Nature

Nature, for Hemingway, was not just a backdrop but a source of wisdom. The discipline of fishing, the patience of hunting, the observation of animals-all these shaped his writing. In the Luxembourg Gardens, he found a different kind of nature: cultivated, ordered, yet still alive with possibility. The movement of light through the trees, the play of children, the quiet persistence of the gardeners-all became part of his meditation.

He wrote, “There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached”. The gardens were a place he returned to, again and again, to find himself.

Reflect

- Where do you go to find clarity?

- What questions are you seeking to answer?

- How do you renew yourself when life becomes overwhelming?

- What role does nature, or a place of beauty, play in your journey?

Exercise: Your Own Garden of Clarity

- Recall a place that gives you clarity.

Write about where it is, what it looks and feels like, and why it brings you peace. - List the questions you are seeking to answer right now.

Are they about your work, your relationships, your purpose, or something else? - Describe a time when stepping away from daily life helped you find a solution or new perspective.

What changed when you gave yourself space to reflect? - Plan a walk or visit to a place of beauty in your own city.

As you walk, let your mind wander. What insights arise? What old patterns fall away?

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Inmost Cave

Imagine yourself now, strolling through the Luxembourg Gardens. The air is fresh, the trees are in bloom, and the city’s noise fades to a distant hum. You are alone with your thoughts, your questions, your dreams. The gardens invite you to slow down, to listen, to seek the clarity that comes only in stillness.

What will you discover in your own inmost cave? What answers are waiting for you, just beyond the next path, the next turning of the season?

Take a deep breath. Trust the journey. Let the gardens guide you inward, to the heart of your own story.

“Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you brought to it. But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

8. Ordeal / The Destroyer

Location: Les Deux Magots (Saint-Germain-des-Prés)

Confront your greatest challenge.

Les Deux Magots: The Crucible of Parisian Literary Life

In the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, under the watchful gaze of two porcelain Chinese figurines-the “magots” that give the café its name-Les Deux Magots has witnessed more than a century of Parisian history. Since its transformation from a silk and novelty shop in the 19th century into a literary café in 1884, it has become a legendary gathering place for artists, writers, and thinkers. Here, the air is thick with the ghosts of debates, arguments, and creative breakthroughs. For Ernest Hemingway, Les Deux Magots was both a sanctuary and a crucible-a place where ideas were forged in the heat of discussion, and where he confronted some of his greatest personal and artistic challenges.

By the 1920s, Les Deux Magots was at its zenith as a hub for the avant-garde. Symbolist poets like Verlaine and Rimbaud had already left their mark, but it was the post-World War I influx of American expatriates-the so-called Lost Generation-that cemented the café’s reputation as a center of intellectual ferment. Alongside Hemingway, figures like James Joyce, André Breton, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Pablo Picasso frequented its tables. The café’s Art Deco interior, with its red banquettes and mirrored walls, became the backdrop for countless literary quarrels, philosophical arguments, and artistic epiphanies.

Hemingway’s Ordeal: The Destroyer at Work

For Hemingway, Les Deux Magots was not just a place to drink coffee or absinthe; it was a battleground. Here, he debated fiercely with friends and rivals, tested his ideas, and sometimes fell out with those closest to him. The café was a crucible for the “fiercely competitive literary prize fight” that Hemingway saw as the essence of writing life.

The Ordeal stage of the Hero’s Journey is about confronting your deepest fears and facing the possibility of failure, rejection, or even destruction. At Les Deux Magots, Hemingway grappled with the challenges of artistic integrity, personal loyalty, and the temptations of Parisian life. The café’s atmosphere-charged with the energy of creative minds and the ever-present threat of rivalry-forced him to confront his own limitations and ambitions.

Hemingway’s circle was full of strong personalities. Ezra Pound and James Joyce were among his closest friends, but he regarded many other American artists in Paris with suspicion, seeing them as “posing artists” more interested in talking than in working. The café was also a place where Hemingway’s relationships were tested-where alliances were forged and broken, and where the line between friend and adversary was often blurred.

The Café as a Stage for Destruction and Renewal

Les Deux Magots was more than a backdrop; it was an active participant in the drama of Hemingway’s Paris. The café’s history is filled with stories of passionate arguments, creative rivalries, and personal crises. It was here that Hemingway and his peers confronted the existential questions of their age-questions about art, love, morality, and the meaning of life after the devastation of war.

The café’s role as a crucible for creative destruction is reflected in its enduring reputation as a home for the unconventional and the rebellious. Since 1933, the Prix des Deux Magots has been awarded annually to a French novel that breaks with tradition, celebrating works that challenge the status quo and embrace the spirit of innovation. This legacy of disruption and renewal is at the heart of the Destroyer archetype.

For Hemingway, the ordeal at Les Deux Magots was not just about external conflict; it was also about internal struggle. The café was a place where he faced his own doubts and insecurities, where he risked failure and rejection in pursuit of something greater. It was here that he learned the value of resilience-the ability to endure criticism, to let go of what no longer served him, and to keep moving forward in the face of adversity.

The Lost Generation’s Ordeal

Hemingway was not alone in his ordeal. The Lost Generation-a term coined by Gertrude Stein and immortalized in the epigraph to The Sun Also Rises-was defined by its sense of dislocation, disillusionment, and longing for meaning in a world that seemed to have lost its way. The cafés of Paris, and Les Deux Magots in particular, became the stages on which these young writers and artists acted out their struggles, searching for integrity in an often immoral world.

The postwar years in Paris were a time of both liberation and loss. American writers were drawn to the city by the promise of artistic freedom and the favorable exchange rate, but they also carried the scars of war and the burden of exile. The Latin Quarter, where Hemingway lived and wrote, was depicted in the press as decadent and depraved-a place where the old values no longer held, and where new forms of art and life were being invented.

In this context, the ordeal at Les Deux Magots was not just personal; it was generational. The café was a microcosm of the larger struggle to find meaning, purpose, and integrity in a world that seemed to have been destroyed and rebuilt overnight. For Hemingway and his peers, every debate, every argument, every moment of doubt was part of the process of forging a new identity out of the ashes of the old.

The Destroyer Archetype: Letting Go to Move Forward

The Destroyer archetype is about the necessity of destruction for the sake of renewal. It is the force that compels us to confront what is no longer working in our lives, to let go of outdated beliefs, relationships, or habits, and to make space for something new. At Les Deux Magots, Hemingway was forced to confront his own limitations and to make difficult choices about what to keep and what to discard.

This process was often painful. Friendships ended, projects failed, and dreams were sometimes shattered. But out of this destruction came growth. Hemingway’s willingness to face rejection, to endure criticism, and to keep writing in the face of adversity was the key to his eventual success. The café’s atmosphere of creative tension pushed him to refine his craft, to clarify his values, and to become the writer he aspired to be.

The Ordeal in Art and Life

The ordeal at Les Deux Magots was not limited to the realm of art. Hemingway’s personal life was also marked by struggle and loss. His marriage to Hadley was tested by the pressures of poverty, ambition, and the temptations of Parisian life. The café was a place where he confronted the realities of love and loyalty, and where he learned the hard lessons of heartbreak and resilience.

The themes of love, loss, and renewal that permeate Hemingway’s work are rooted in his experiences at places like Les Deux Magots. In The Sun Also Rises, he explores the wounds of his generation-the sense of being “battered but not lost,” the search for integrity in a world that often seems devoid of meaning. The café, with its history of creative destruction and renewal, is both a symbol and a setting for these struggles.

Reflect

- What is your greatest fear or obstacle right now?

- What must you let go of to move forward?

- Where in your life are you being called to confront what no longer serves you?

- How can you embrace the spirit of the Destroyer to create space for renewal and growth?

Exercise: Facing Your Ordeal

Write about a time you confronted a major challenge or faced rejection.

- What was at stake?

- What did you have to let go of-an idea, a relationship, a belief?

- How did the experience change you?

- What strengths or insights did you gain from the ordeal?

Take time to reflect honestly. The ordeal is never easy, but it is essential. It is the crucible in which your legend is forged.

The Legacy of Les Deux Magots

Today, Les Deux Magots remains a vibrant part of Paris’s cultural life, its walls adorned with portraits of the great writers and artists who once sat at its tables. The café continues to host literary events, award prizes, and inspire new generations of seekers and creators. Its history is a testament to the power of confrontation, destruction, and renewal-a reminder that greatness is achieved not by avoiding challenges, but by facing them head-on.

To sit at Les Deux Magots is to join a lineage of warriors-those who dared to debate, to risk, to fail, and to begin again. It is a place where the past and present meet, where every cup of coffee is a toast to the courage of those who came before.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Ordeal

Imagine yourself now, sitting at a table at Les Deux Magots. The air is thick with history, the echoes of arguments and laughter still lingering. You are at a crossroads, facing your own ordeal. The city waits outside, full of possibility and peril.

What challenge will you confront? What will you risk? What will you let go of to move forward?

Take a deep breath. Embrace the ordeal. Let the Destroyer clear the way for your next act.

“Creating, is living twice.”

– Albert Camus (on the wall at Les Deux Magots)

List three things you love about your journey so far. How can you savor them more fully?

9. Reward / The Lover

Location: Café de Flore

Embrace joy, connection, and the fruits of your courage.

Café de Flore: Paris’s Temple of Pleasure and Connection

After the storms of rivalry, debate, and creative struggle at Les Deux Magots, Hemingway and his circle often crossed the narrow Rue Saint-Benoît to Café de Flore, the other great literary café of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. If Les Deux Magots was the crucible, Café de Flore was the reward: a place to savor the fruits of hard-won courage, to bask in the warmth of friendship, and to celebrate the joys of the present moment. Here, the Lover archetype flourished, inviting all who entered to embrace life’s pleasures and connections.

Founded in 1885, Café de Flore is named after the Roman goddess of flowers, a fitting symbol for a place dedicated to beauty, conviviality, and renewal1. Its red banquettes, mahogany furniture, and brass railings have changed little since the 1930s1. The café’s terrace, always bustling, has played host to generations of artists, writers, and philosophers. If the walls could speak, they would tell of laughter, romance, and the kind of deep, searching conversation that turns strangers into friends and friends into legends.

The Café as Reward: Joy After the Ordeal

For Hemingway, Café de Flore was a sanctuary after the ordeals of artistic creation and existential debate. Here, he could relax, enjoy good food and strong coffee, and let down his guard. The café was quieter than its rival, a place where celebrities and thinkers could retreat from the crowds and simply be themselves. Hemingway was not alone in seeking solace here; Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir famously called it “home,” spending entire days writing, talking, and watching the world go by.

The reward stage in the hero’s journey is about embracing the gifts that come after struggle: pleasure, connection, and the sense of having earned a place at the table. At Café de Flore, Hemingway celebrated not only his own successes but also the joys of community and belonging. The café became a symbol of the “moveable feast” he described in his memoir-a banquet for the senses, a celebration of life’s fleeting but unforgettable moments.

The Lover Archetype: Savoring Life’s Richness

The Lover archetype is about more than romance; it is about the capacity to experience joy, to open oneself to beauty, and to connect deeply with others. In the context of Hemingway’s Paris, the Lover is the part of us that delights in good food, stimulating conversation, and the pleasures of friendship. It is the archetype that says yes to life, even after hardship.

At Café de Flore, Hemingway and his contemporaries-Fitzgerald, Picasso, Capote, Camus, and so many others-let themselves be nourished by the city and by each other. They celebrated victories, mourned losses, and found comfort in the rituals of café culture: the clink of cups, the aroma of coffee, the taste of a simple meal shared with friends. The café was a place to remember that, even in a world marked by loss and uncertainty, joy was still possible.

The Fruits of Courage: Connection and Celebration

The reward for Hemingway was not just literary success, but the richness of connection. At Café de Flore, he found a community of kindred spirits-people who understood the struggles and triumphs of the creative life. The café’s history is filled with stories of friendships formed, romances kindled, and ideas that would shape the world13.

The café was also a place of celebration. After the publication of a new story or the completion of a difficult chapter, Hemingway would treat himself to a good meal or a glass of wine. He understood the importance of marking milestones, of pausing to acknowledge progress before moving on to the next challenge. Café de Flore became a stage for these small but significant acts of self-recognition-a reminder that the journey is as important as the destination.

Café de Flore Today: A Living Legacy

Café de Flore remains a pillar of Parisian café culture, its terrace still crowded with writers, artists, and travelers seeking inspiration. The café has barely changed since Hemingway’s time, and its atmosphere of creative possibility endures. Today, it is not only a place to remember the past but also to create new memories, to celebrate your own journey, and to connect with the spirit of those who came before.

The café even awards its own literary prize, the Prix de Flore, to promising young authors-a testament to its ongoing role as a cradle of creativity and connection. To sit at Café de Flore is to become part of a living tradition, to taste the sweetness of reward after struggle, and to honor the Lover in yourself.

Reflect

- What brings you joy and connection?

- How do you celebrate your progress?

- Who are the “lovers” in your life-the friends, mentors, and companions who help you savor the journey?

- How can you create more moments of celebration and connection in your daily life?

Exercise: Celebrate Your Journey

List three things you love about your journey so far. How can you savor them more fully?

- Joyful Connections:

Who have you met along the way who has enriched your life? How can you nurture those relationships? - Personal Triumphs:

What milestones-big or small-have you achieved? How can you honor those victories? - Moments of Beauty:

What experiences, places, or rituals have brought you happiness? How can you make space for more of them?

Take time to reflect and write. Consider treating yourself to a small celebration-a meal, a walk, a conversation with a friend-to mark your progress and honor the Lover within you.

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Café de Flore

Imagine yourself now, seated on the terrace at Café de Flore. The city hums around you, the sun glints off the green and white china, and the air is alive with possibility. You are surrounded by the echoes of those who came before-artists, lovers, dreamers-and you are part of their story now.

What will you celebrate today? Who will you share it with? The table is set, the feast is moveable, and the reward is yours to savor.

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

10. The Road Back / The Creator

Location: Brasserie Lipp

Begin to shape your own legend.

Brasserie Lipp: Where Stories Become Legend

On the Boulevard Saint-Germain, beneath the green and gold sign of Brasserie Lipp, Paris’s literary and artistic history gathers in the clink of glasses and the hum of conversation. For Hemingway, the brasserie was more than a restaurant-it was a creative crossroads, a place where hunger, hope, and the forging of a personal legend converged. Here, after the rewards and connections of Café de Flore, the journey bends toward the future: the road back, the return to daily life, but now as a creator, a legend in the making.

The Hungry Years

In the early 1920s, Hemingway and Hadley were often desperately poor. Paris was a city of feast and famine, and for much of their time, it was famine. Hemingway, a natural heavyweight, would walk the city to distract himself from hunger, sometimes wandering through the Palais du Luxembourg to gaze at paintings instead of shop windows filled with food. When a check arrived or an article sold, he would splurge at Brasserie Lipp-drawn by the promise of a hearty Alsatian meal, a liter of cold beer, and the sense of abundance that only the truly hungry can know.

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway describes these moments with gratitude and delight: the potato salad, the beer, the feeling of being restored. The brasserie’s Art Nouveau interior-mirrored walls, palm tree murals, purple moleskin banquettes-remains largely unchanged, a living link to the days when Hemingway and his circle shaped the future of literature over plates of choucroute and cervelas remoulade. The décor, the staff, the rituals of service: all conspired to make Brasserie Lipp a stage for creation, connection, and the birth of legend.

The Creator’s Table

Brasserie Lipp was not just a place to eat. It was a place to create. Hemingway and his peers-Fitzgerald, Joyce, Pound, and others-gathered here to share stories, argue about art, and imagine new futures. Every meal was a chance to test ideas, to shape manuscripts, to turn the raw material of experience into the stuff of legend.

Hemingway’s writing style-direct, unadorned, “meat and potatoes”-mirrored his meals at Lipp5. He believed in writing the “truest sentence you know,” in stripping away the inessential, in letting the story speak for itself. The brasserie’s hearty Alsatian fare, its robust beer, and its no-nonsense service became metaphors for this approach: honest, satisfying, and deeply rooted in tradition.

But the brasserie was also a place of transformation. Here, Hemingway could step outside the struggles of poverty and obscurity and imagine himself as the writer he wanted to become. Every story told, every toast raised, was a rehearsal for the legend he was shaping-a legend that would one day be known around the world.

The Road Back: Returning as a Creator

In the hero’s journey, the road back is the return to the ordinary world, but now transformed. The hero brings with them the “elixir”-the wisdom, strength, or creativity gained through ordeal and reward. For Hemingway, the road back led from the brasserie’s warmth and camaraderie to the solitude of his writing desk, from the laughter of friends to the silence of the page.

But he returned changed. The stories shared at Brasserie Lipp, the encouragement of peers, the rituals of celebration-all became fuel for his next creative act. He learned that creation is not a solitary endeavor, but a communal one: shaped by conversation, by rivalry, by the shared pursuit of something lasting and true.

The brasserie also became a place of legend in its own right. Its tables witnessed the birth of novels, the forging of friendships, the settling of literary scores. Hemingway once joked that if anyone wanted to find him-or even shoot him-they could do so at Brasserie Lipp, between two and four every day. The bravado was real, but so was the sense of belonging, of having carved out a place in the city’s creative heart.

The Legacy of Brasserie Lipp

Brasserie Lipp remains a Parisian institution, its menu still offering the classics Hemingway loved: herring with potatoes in oil, choucroute garnie, roast chicken, and more. The interior is a time capsule, its Art Nouveau details unchanged, its staff still moving with the practiced choreography of a century of service. The brasserie sponsors the Prix Cazes, an annual literary prize, and continues to attract writers, artists, and travelers from around the world.

To sit at Brasserie Lipp is to join a lineage of creators, to feel the pulse of Paris’s artistic life, and to remember that every legend begins with a story, a meal, a moment of courage.

Reflect

- How are you shaping your own story?

- What legacy do you want to build?

- Who are your creative allies, and how do you support each other’s dreams?

- How do you turn the raw material of your life into something lasting and true?

Exercise: The Creator’s Inventory

- List three things you’ve created or accomplished on your journey so far.

What do they mean to you? How did you bring them into being? - Describe a moment when you turned adversity into creativity.

What resources did you draw on? What did you discover about yourself? - Imagine your own “brasserie”-a place where you gather with allies to share ideas and shape the future.

Who is there? What stories do you tell? What dreams do you dare to speak aloud?

Walking in Hemingway’s Footsteps: Your Own Legend

Imagine yourself now, seated at a table in Brasserie Lipp. The air is thick with history, the laughter of friends and the clatter of plates echoing through the room. You are part of a living tradition, a creator among creators. The city outside is full of possibility, and your story is yours to shape.

What will you create next? What legend will you leave behind? The road back is not the end, but the beginning of your next act.

“Begin as you mean to go on, at a bar.”

– Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

11. Resurrection / The Ruler

Location: Montparnasse Cemetery

Rise renewed, claiming your authority.

Montparnasse Cemetery: The Garden of Legends